Episode 8 - ASP.NET Core

Embedded Player

The .NET Core Podcast

Episode 8 - ASP.NET Core

Supporting The Show

If this episode was interesting or useful to you, please consider supporting the show with one of the above options.

Episode Transcription

Hello everyone and welcome to THE .NET Core podcast - the only podcast which is devoted to:

- .NET Core

- ASP.NET Core

- EF Core

- SignalR

- and not forgetting The .NET Core community, itself

I am your host, Jamie “GaProgMan” Taylor, and this is episode 8: ASP.NET Core. In this episode, I’m going to introduce ASP.NET, talk about what the Core version is and how it relates to the .NET Framework version.

So let’s sit back, open up a terminal, type dotnet new podcast and let the show begin.

Introduction

If you’re new to the podcast, then you might not know about it or me. So I’m doing to take a moment and talk to you about both:

I’ve been writing about .NET Core over at https://dotnetcore.gaprogman.com for almost 2 years (at the time or recording this episode).

I’m a developer from the .NET Core community who really digs on the “core” technologies and is a little bit evangelical about them.

In fact, it’s the reason why I started this podacast. For a fuller introduction to me, why I started this podcast, and what I’m hoping to achieve with it, you should check out episode 0 (I’ll leave a link in the show notes, so be sure to check your podcatcher of choice).

The show notes for this episode will include a full transcription and some useful links, so don’t forget to check them out too.

In this episode we’ll talk a little bit about ASP.NET, what it’s about, and what MVC, Razor and Blazor are. We’ll cover a little history and talk about what ASP.NET Core is and how you can use it in your applications (both .NET Framework and .NET Core, as we’ll see).

Let’s talk about ASP.NET Core - right after this.

So What Is ASP.NET?

If you’re old enough, then cast your mind back to the mid 90s. Sony’s PlayStation had just come out and (unfortunately in my opinion) whooped the backside of the Sega Saturn; Toy Story, Pocahontas and GoldenEye were rocking the box office; and Alannis Morrisette and Oasis had made a big splash with their debut albums.

But this was the dark ages of the Internet.

The initial version of JavaScript had recently been released, and it was a long way from the version of JavaScript that we use today, and behaved differently in the different browsers. On the server, we had the choice between static sites or PHP powered pages - both of which could make use of the new Common Gateway Interface - but only small portions of each page could be dynamically created based on a subset of features available to web developers of the time.

This was before AJAX, before Bootstrap (or whichever your front end CSS framework of choice is), and even before jQuery. If you wanted to make your site work on Internet Explorer, you may have needed to include IE specific hacks - we kind of still have these to this day in the form of shims, but these are less widely used as the support for the older browsers has been dropped.

Pages were covered in marquees, animated gifs (that’s right, I pronounce it with a hard g), and it was extremely important to have a guest-book.

Then along game blogs, with their “FIRST!” comment wars. And Flash with it’s security issues, but my goodness was it ever fun to play those stupid games - I mean, “use the Internet to look up things that I needed for school”.

Enter: Scott Guthrie

Over the Christmas break of 1997, Scott Guthrie and fellow Microsoft engineer Mark Anders came up with a technology that they called XSP (which stood for Cross-Site Printing). It allowed IIS (that Microsoft’s Internet Information Service - a Microsoft based webserver and reverse proxy technology) to serve dynamic web pages. This technology would be re-branded as ASP (or Active Server Pages) before being made available to customers.

Essentially, the innovation here was that a developer could write code which could intercept the incoming HTTP requests, use information found within it and any supporting cookies, and script the creation of HTML responses.

What really set ASP apart was the use of Session and ViewBag variables. To all of us doing modern web development this is almost a given, but back then the ability to store data about all of the requests and responses for a given user at a given time (sometimes called a User Journey), was golden. Finally, you could tailor pages to individual users and offer up truly dynamic content based on who that user was.

To be fair, this was doable back in the dark ages of the Web but it came at a price, and this price was creating a lot of server side pages or leveraging things PHP. But now, it could all be scripted using either VBScript (a variant of Visual Basic, but used for scripting), JScript (which was essentially a subset of JavaScript created by Microsoft), of PerlScript (a variant of ActivePerl).

OK, so the syntax could be a little terse but it was pretty similar to the bare bones HTML that most web developers were writing at the time - especially since this was the days before things like DreamWeaver became popular.

As we reached the millennium, version 3 of ASP was released but Microsoft was betting big on something new that they were cooking up.

ASP.NET

In 2002, Microsoft released ASP.NET alongside the very first iteration of the .NET Framework. The fact that it was released alongside version 1.0 of the .NET Framework was no accident - it used the very same Common Language Runtime that applications built with the .NET Framework did.

It also uses System.Web.dll, which was included as part of the .NET Framework

Where ASP allowed you to build dynamic HTML pages (I’m not doing a good job of selling how big of a deal this was, or the amazing things that people could build with it, by the way), ASP.NET would allow you to do so much more.

Essentially, ASP.NET would intercept the incoming requests and create an instance of what’s called the <code>HttpContext</code> object for each of those requests. That object would then be passed to a pipeline that you created, information within the HttpContext object contained the requested URI, query string, any cookies, and related session data.

There was a technology called Web Forms, which allowed you to create and use what were called “server controls”. These server controls could be embedded in a page with a shortcode, they would render HTML, and could be used to respond to user actions (via Post Back messages). You can think as these as similar to components in modern web development.

Web Forms was completely stateless (as is HTTP), so the <code>ViewBag</code> was invented to alleviate this - this was essentially a dictionary which would allow you to store any value between those post backs; however it would be sent to and from the server as part of both the requests and responses, which obviously could increase page load time.

There was a technology called Web API, which allowed you to write RESTful APIs in any of the .NET Framework languages. This no longer meant that you had to use CGI to generate responses in low level code, you could leverage the .NET Framework’s abstractions to do most of the hard work for you.

SignalR (which will have an entire episode of it’s own) blew the doors off of what the web could do, and came much, much later. Essentially, SignalR sets up long polling (as well as a bunch of other stuff), so that you could have real time, bi-directional communication between a client and a server over the web.

And then there was MVC

Model-View-Controller

If you’ve ever used the Ruby on Rails, Django or Java Spring frameworks then MVC will be familiar to you.

MVC is a fantastic abstraction for the web - it’s not the only one, there’s MVVM, Presenter Abstraction, and Model-View-Presenter too - there are a bunch of others, of course. It can be used on desktop or mobile as well, but you’ll more often than not find it on the web.

MVC is split into three parts:

- Model

- View

- Controller

Essentially the user interacts with a Controller by sending an HTTP request; the Controller creates a Model (usually in the form of a POCO - that’s a Plain Old C# Object); which is then combined with a View to create an HTTP response for that request.

The ASP.NET version of MVC is what’s known as a thin client, this means that all of the heavy lifting is done at the server side. The client (in this instance a browser) sends HTTP requests to the server, and the server creates and returns all of the content. Frameworks like Angular and Ember are the opposite of this as these frameworks require some of the MVC components to be present at the client side.

Most of the websites that you’ve interacted with in the past 20 years will have been MVC based - unless they were static sites, or Single Page Applications.

ASP.NET Core

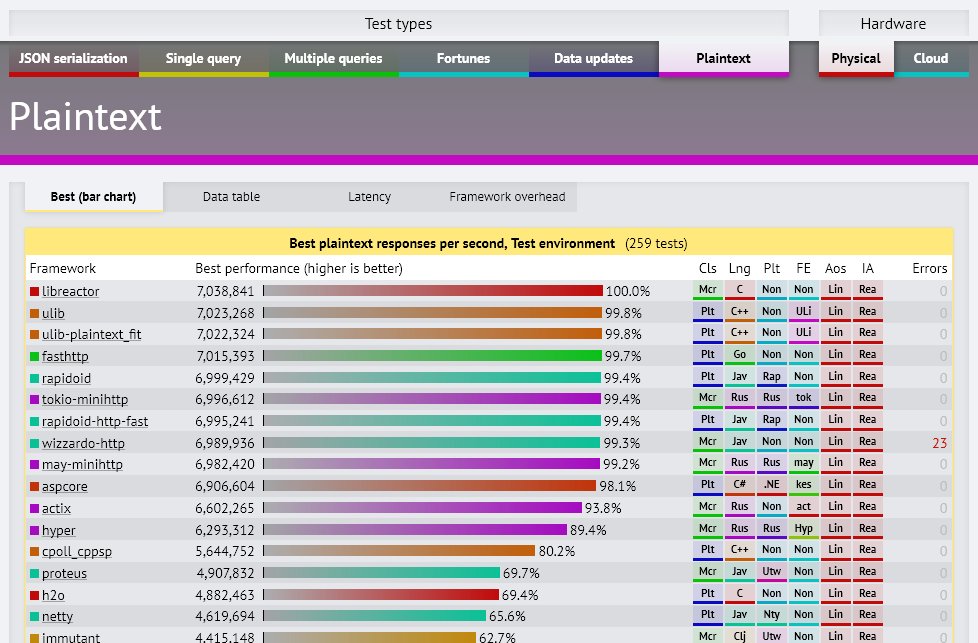

ASP.NET Core is the latest iteration of ASP.NET. Essentially, it’s an open source rebuild of ASP.NET with a focus on speed and cross platform compatibility. At the time of recording, Round 16 of the TechEmpower benchmarks have completed. These are number of benchmarks designed to show off which web frameworks are the fastest, and ASP.NET Core is placed at 10th for plain text requests (which means it’s able to serve 6,970,937 requests per second).

Although, it’s a “core” technology (my short hand for .NET Core, ASP.NET Core, and EF Core, SignalR, Blazor, those kinds of things) it can also be used with either .NET Core or .NET Framework. This is because it does away with the use of System.Web.dll, which is what ASP.NET used and is supplied as part of Windows.

Where ASP.NET uses System.Web.dll (with all of it’s Windows based API hooks), ASP.NET Core uses a new web server called Kestrel. Kestrel was initially built on libuv, this was because of the cross platform nature of libuv.

However with the release of ASP.NET Core 2.1, the ASP.NET Core team moved away from libuv and began offering Kestrel based on managed sockets. This was for a number of reasons, including (but not limited to):

- Broad platform support. Wherever managed sockets are supported, Kestrel should work. Doesn’t require recompiling libuv to bring up a new OS.

- Helps to drive improvement to the .NET sockets implementation, which benefits anyone else using managed sockets.

the above points are taken from this GitHub comment

Cast your mind back to episode 1, when I talked through a brief history of .NET (see the show notes for a link, and I included the following quote from an ASP.NET Community Standup:

DAMIEN: Um. But this isn’t just about being you able to develop ASP.NET on a Mac

HANSELMAN: I See

DAMIEN: We’re looking beyond that.

HANSELMAN: Ok, so for now…

HUNTER: I want you to host apps on Linux Servers, that’s my

DAMIEN: You heard it from our boss

HUNTER: That’s my goal, is I want you to be able to host ASP.NET app on a Linux server as easily as you can on a Windows server

This could never have been possible using System.Web.dll, but is completely possible using Kestrel.

Because ASP.NET Core is built with the same modular nature as .NET Core in mind, you can include just enough of it to run your application. This is a big change from ASP.NET which need to be included with your source code regardless of how much of it that you were using.

Another benefit to using ASP.NET Core over classic ASP.NET is that MVC and WebApi have been combined into the same namespace. When using ASP.NET, MVC controllers needed to be separate from WebApi controllers. Whereas in ASP.NET Core, WebApi, MVC and Razor Pages (which we’ll cover in another episode) are essentially the same thing.

Wrapping Up

We’ve covered the basics of what ASP.NET Core is, how it relates to ASP, ASP.NET and .NET Framework. We’ve talked through a brief history of ASP and a few of the things that ASP.NET offered to web developers.

We’ll cover the types of applications that you can create with ASP.NET Core in a later episode.

One thing to remember about Kestrel though, is that it is not “battle ready”. That means that it hasn’t been hardened against common Internet attacks. As such, it is recommended (at least, at the time of recording this episode) that you still host your ASP.NET Core applications behind a “proper reverse proxy and webserver combo” (things lik Nginx or Apache come to mind).

Anyway, that’s going to do it for this episode. Hopefully you’ve found this interesting, if you did then let me know by sending me a tweet @dotnetcoreblog, or head over to the website dotnetcore.show and let me know what you think.

Remember to check the show notes for a link to the full transcription of this episode and links to a bunch of related websites and resources. These is available at dotnetcore.show.

And don’t forget to spread the word, leave a rating or review on your podcatcher of choice, and to come back next time for more .NET Core goodness.

I will see you again real soon. See you later folks.

Useful Links

- YouTube version of this episode

- The YouTuve version of this episode in case you’d prefer to listen there.

- Episode 0 - An Introduction to the Podcast

- This episode explains more about who I am and why I created the podcast.

- TechEmpower Round 16 results

- Episode 1 - A Brief History of .NET Core

- ASP.NET Core In Action

- This is an wonderfully well written book on ASP NET Core, by Andrew Lock

- I would definitely recommend it.

- https://twitter.com/dotnetcoreblog