Episode 25 - Blazor - You Want To Run .NET Where?!

Embedded Player

The Modern .NET Show

Episode 25 - Blazor - You Want To Run .NET Where?!

Supporting The Show

If this episode was interesting or useful to you, please consider supporting the show with one of the above options.

Episode Transcription

Hello everyone and welcome to THE .NET Core podcast - the only podcast which is devoted to:

- .NET Core

- ASP.NET Core

- EF Core

- SignalR

and not forgetting The .NET Core community, itself.

I am your host, Jamie “GaProgMan” Taylor, and this is episode 25: Blazor: You Want To Run .NET Where?!. This episode is a shortened version of a talk I did at Umbraco Festival 2018 on Blazor, it covers a little of the history of how we got from no CSS and JS to using HTML and CSS in our JS, all the way up to using .NET in the browser.

This episode was an edited version of the talk that I gave at Umbraco Festival 2018 on Blazor. Check out the show notes for a link to the full video version of the talk, which The CogWorks have graciously allowed me to use for this episode. So my thanks go to them for allowing me to use the audio, and for running the Umbraco Festival and allowing me to talk there.

Just before we begin, did you know that the show has a mailing list and a Slack group? why not sign up for the mailing list or join the Slack group by following the links in the show notes?

So let’s sit back, open up a terminal, type in dotnet new podcast and let the show begin.

Introduction

Hello everyone!

Can you hear me first off? Because I’ve got a bit of good a bit of a sore throat today, so I apologise. Closer to the mic? Ok, how about now?

Ok, yeah, so I’m Jamie Taylor. I do have a sore throat, so I may have to cough and then come back. I have been trying to clear the sore throat all week, but it’s just not wanting to move. Tomorrow morning I will wake up and it Won’t be hurting it all. I’ve got all sorts of meds with me today to try and help that.

So today, I thought that I’d talk to you about Blazor, which is a new Microsoft, well “new”, Microsoft technology - you’ll see later that it isn’t even vaguely new, but there you go.

A Little History

So the first part. So this is gonna be divided into to parts, I’m gonna really quickly go through a little bit of HTML, JavaScript, and CSS to see how we got to where we are, and then I’m going to talk about Blazor and show off two demos. One is hopefully related, so it’s not just gonna be completely boring.

I am @dotnetcoreblog on Twitter and I run The .NET Core podcast, which is the t-shirt that I’m wearing.

[“woo” from a person in the audience]

Oh yes. So if anybody wants to talk about .NET Core, ASP.NET Core, EF Core, SignalR or anything like that, come and have a chat with me. I’d love to interview you for the podcast, talk to you on the podcast, that be fantastic. Hopefully the first bit won’t take too long, I’m going to really quickly breeze through it. All of the slides are already on GitHub because it uses MarkDown and RevealJs. I’ll send the link around on Twitter later on. So definitely pull the code down on, and have a look.

And when you’re looking through them hit s on your keyboard, you get these really cool slide notes. I’ve put loads of stuff in. Each slide has a bunch of notes already, they’re mainly a prompt for me, but it’s also a little bit on there.

So if you can figure out what:

In which Doris gets her oats

is from without using Google, you can get a .NET Core sticker from me, or just come up to me and say, “I want to sticker!”, and I’ll give you a sticker.

[laughter from the audience]

Just really quickly about me I’m a .NET Core maniac - that’s how I’ve been described. I am a serial podcast creator. I’ve got The .NET Core Podcast; The Waffling Taylors Podcast, which is me and my brother talking about video games; and DevOtaku which is me and a few of my friends talking about, like relaxing in, and finding ways to relax and disconnect from the tech industry. But that’s not what I’m talking about today. Hopefully this is going to be really quick:

When HTML started everything was static, and it was all good. In fact, if you Google for it the SpaceJam website is still live, and it is all HTML tables the entire site is HTML. There is some JavaScript on there now, which is Google Tag Manager, which is how they know they need to make a sequel because everybody keeps hitting the website, and they’re going:

Wow! People in their 20s to 40s want a Space Jam sequel!

So well done, everyone. We’re getting SpaceJam sequel. If you have never seen SpaceJam, don’t.

[laughter from audience]

So back in 1994, we were essentially told there was gonna be no styling other than inline styling. I’ve got this directly from, check the show notes and stuff, and check the links, and that. We’re essentially told:

Sorry you’re on your own. You just like TeX, there’s nothing other than in line styling.

And then, less than a year later, there was a W3C group all about creating style sheets and cascading. So, you know, the idea that this technology is constantly changing constantly in flux.

And just a little bit of history: at the same time that that was going on, Dolly the sheep was being cloned. Internet Explorer three supported CSS before it was released, so well done, I guess. And then CSS level one was ratified in 1997.

We can’t blame Brendan Eich because JavaScript came along and it was not a number. He was tasked with creating a server side, almost like a, scripting language, and he was fighting against Pearl and other people, and he was given ten days to come up with the basic version of it, and he released it and all of the browsers went:

That’s fantastic. Why don’t we not implement that and implement our own version?

Which is why, yeah, that’s why we have all the different browsers, or used to have different support for different things. Why we ended up with different versions of the standard, and back in the day in the late 90s to early 2000s, if you inspected pages, it was, you know, we still them now, the: <!--[if lt IE 9]> then load this JavaScript in, to be able to load the page. It’s also why, in the late 90s, we always had the little badges, and usually the bottom right hand corner:

This website works best with IE7

or:

This website works best with NetScape

and stuff like that.

Then along came the ECMA standard and nothing changed. Version fous was abandoned for a bunch of political reasons. And then we have more ECMA standards, there’s too many standard versions. And then at least you know where the naming standard comes from: it’s not even related, ES6 is ES2015 because why not, let’s do version numbers.

And then came jQuery, and we went:

Fantastic. Finally, a system that allows us to run any kind of JavaScript on any kind of browser. That’s brilliant!

Except the first version of it was 90Kb, and you thinking, “that’s not a lot.” Well version three, the current LTS version, is 86Kb. If you want to use AMP you’ve got a 50Kb JavaScript Limit. You can’t include jQuery, so you’ve got a ditch, all of that. Maybe you can compile your own version, and just include the stuff you want, but even so.

And then along game the UI frameworks, and all of them required jQuery to work. So we’re like:

we’ve got this huge dependency now. We’ve got this monkey patching system. What’s going on? I can’t deal with this, it’s too many things.

And then nodejs on a satellite, because that makes sense. Can you imagine? A satellite crashes into your house and the developer goes:

Sorry. I Didn’t do a check for not a number. And then that’s why you’re has been trashed

Then we wanted type safety. So we’ve got a transpiler, so you can write something in a different language and compile into JavaScript. Obviously the last two are joke ones. You know, ArnoldJs is all Arnie quotes and TrumpJs is making JavaScript great again. But the first three are transpilers, you can write something in CoffeScript and it will be type safety-ish. And then you compile it down to JavaScript and there’s lots of extra code. But the problem is all this extra code just to do the basic stuff, right.

And then we get single page applications. We’ve got so much of this stuff loaded into the browser, and it’s just getting a bit crazy. So SPAs are brilliant, except to be able to load the page, got to download all of this JavaScript. And if you’ve done it wrong, like some people I know - maybe I work with them, maybe I don’t, I can’t actually say whether I do or not - you end up with a SPA that has 20MB of JavaScript just to load the login page. And then, if you can’t login, you’ve wasted all of that time loading stuff - and that’s all minified and uglified.

And then in 2010 Chris Dunelm goes:

Why can’t we just have .NET in the browser? That’d be fantastic wouldn’t it?

so he started this project .NET Anywhere. And the idea was to cross compile the .NET Framework in its C and C++ code over to

WebAssembly, which was just sort of being ratified and thought about. So WebAssembly I’ll come on to in a minute, is a way of running binaries in the browser, which is genius. Obviously, there’s going to be security holes, there always are. But the idea is that it is a walled garden sort of JavaScripty run time. But JavaScript has a bunch of stuff where you can go get the GPS location, and take payments.

So the problem with this was that you had to download the entirety of .NET Framework, before it will run you app in the browser, so that took a while.

So then along came Steve Sanderson, who went:

Hey, I’ve done this thing called KnockoutJs and it’s fantastic. I’ve heard about this thing called .NET Anywhere. There might be something in it. Maybe I could take the knowledge I know about making a JavaScript framework and make this a little better. Plus I kind of work from Microsoft anyway. So maybe I could do something there.

Meanwhile Xamarin got bought by Microsoft along with Xamain came Mono. There’s a huge history of like how Microsoft bought Mono, and the deal that they got, and it’s a bit crazy, really. But essentially .NET Framework has always been a thin wrapper around the Windows 32 programming API. Mono didn’t have that because it was explicitly designed to run on Unix systems. So Mono has everything you need from the high level stuff that we write as .NET developers, all the way down to the lower level C code and assembly to actually make those things happen. So they went:

why don’t we cross compile that to Web assembly, and we’ve got a tiny .NET environment that already doesn’t need the Windows 32 APIs.

So my mate Paul Seal, who’s giving a talk out there, we were both at Hack24 on the same weekend that WebAssembly was officially announced. We were busy losing at Hack24 - I’m not better about it all. But webAssembly allows you to have a sandbox similar to like a JavaScript runtime: you just throw a pre-compiled binary at it, this compiled binary could be from C code, from Dart, from Go, from C#, whatever want, it will run at native speed in the browser. Which is fantastic. The only drawback is you gotta download the binary, which could take a while, and you can’t really compress them because it’s already compiled.

What Is Blazor

So what is Blazor? So imagine you could do UI stuff without having to use JavaScript.

[laughter from audience]

I know, right. This is a promise we’ve been given for decades: UI without the JavaScript. But that’s entirely what it is. So imagine you could do that, imagine that you’ve got .NET in the browser, imagine being able to do stuff on the server, and the data being sent across to the client; so the client doesn’t actually have to do anything, you could just:

Here’s the view. Just show this view, not a problem.

And that’s what Blazor. It’s also a combination of Browser and Razor, because it’s this idea of running the actual razor in the browser.

And then there was an ASP.NET Core Community standup showing us the public preview. If you don’t watch the ASP.NET Community standups and you’re interested in .NET/ASP.NET, regardless of whether his Framework, Core, Mono, or Xamarin, you should definitely watch it. It’s live.asp.net they’re vaguely every week on a Tuesday, usually it’s really late at night, but it’s totally worth watching because you get to learn all of the new stuff that’s coming out, if you’re not an MVP. It’s Scott Hanselman, and John Galloway, and Damien Edwards sit around a table and discuss:

So the next version of .NET is gonna have this, and this is how it works

And they go into loads of detail. They also make fun of each other for the different microphones they use.

So NDC Oslo 2017, the bomb was dropped. I say the bomb, obviously not really. Steve Sanderson. That’s a link that, you can click it, and go watch it, again go pulldown the slides and go have a look. But essentially is an hour and 20 minutes of Steve Sanderson going:

Wouldn’t it be great if we could do .NET in the browser

And he blows everyone away with this

Hey, look, here’s this app that’s running in the browser.

If you haven’t seen that talk and you have an hour and 20 minutes spare, most of you guys will have travelled down on a train, watch it. It is amazing, because he was a much better job of describing Blazor than I do. But this was absolutely huge .NET in the browser. That’s mad. You can’t get compiled binaries in the browser. Well, yes you can. And is the full .NET as well. It’s not just this API and this, it’s the whole thing, the complete shebang, everything you might want.

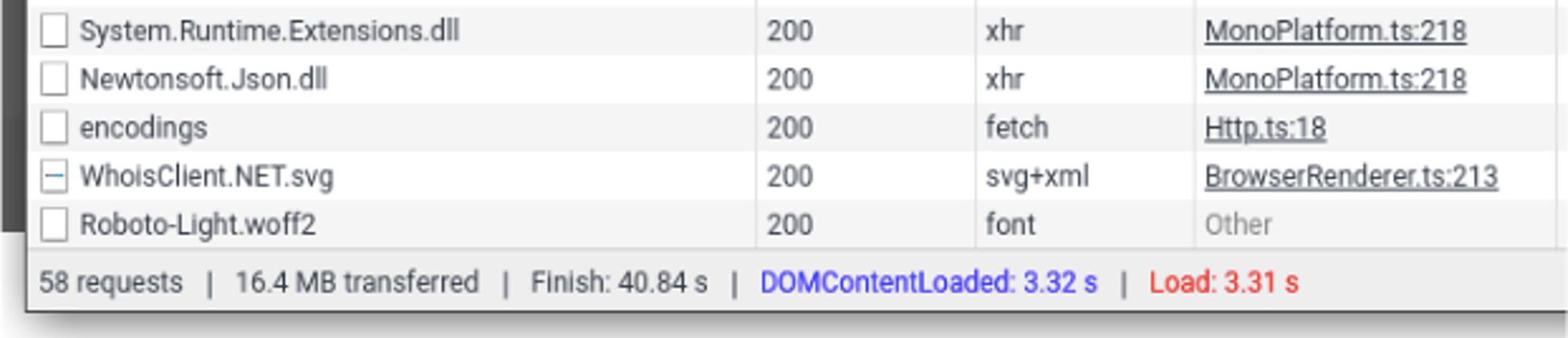

But how does it work, right? I’m talking about how this Blazor thing is brilliant, but I haven’t actually discussed how it works. Well, what happens is obviously your browser downloads the HTML. The HTML includes a tiny JavaScript file which bootstraps another JavaScript file, which pulls down mono.js. So mono.js pulls down the mono WebAssembly, so this is a compiled version of Mono for WebAssembly. In then passes that to the browser. It then does some shim stuff in case you’re on Microsoft browser because they don’t quite fully support WebAssembly. I mean they do Edge does, but IE doesn’t. And it does some stuff where it loads in the Mono runtime and sets up an entire runtime ready for your app. It then goes, “Right, give me the app dll.”

And for those of you don’t know how the GAC works - the global assembly cache - when you start your app .NET, or Mono, or whatever, will look in the local directory for whatever dlls it needs, and for the versions it needs. If it doesn’t find them there it’ll go globally, and if it doesn’t find them there, it’ll go university; looking in a wider path.

So what the Mono runtime does is it goes:

Hey, I need

system.linq. Hey I neednewtonsoft.json. Hey, I need this, and I need this.

And it’ll pull it from server. So you could supply the very specific version of the that dll, the same way that you would ship the very specific dll with your websites, with desktop apps.

And then it will boot that up, and then it’ll start creating a virtual DOM in the same way that, like React and angular do. And it will create a render tree, and every time something changes, it doesn’t do a full page refresh, it’ just goes:

Hey, this is that one component here has changed. Send it through to the browser.

The browser there will just change that one component which saves on memory usage, it saves on all sorts of stuff. Again, it’s an angular thing, an angular and React thing. It’s not new.

But the problem is that dlls a huge. I don’t know whether you can see it there but newtonsoft.json adds over 16Mb of dlls. That’s ridiculous, right? You don’t want to do that.

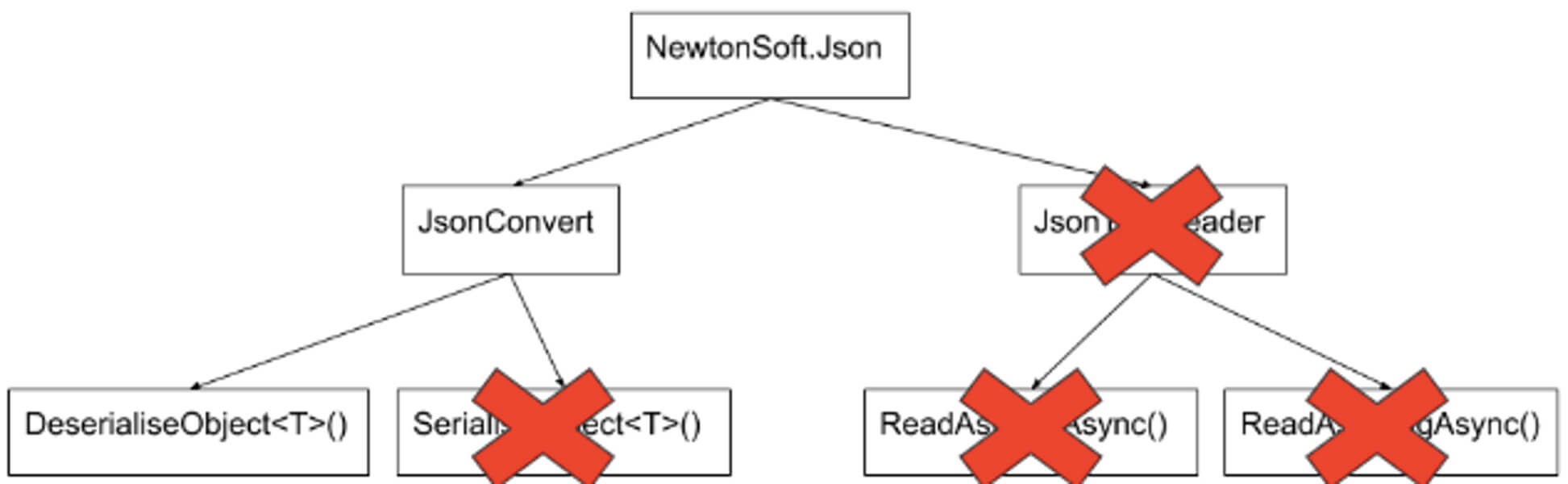

Before the 2.1 preview there was no such thing as IL Shaking. In 2.1 onwards, we now have IL Shaking for Blazor, which is fantastic. It’s kind of like tree shaking, it’s the same kind of idea. Also, don’t include 15Mb of .NET packages, because that’s just ridiculous.

Essentially IL Shaking, for those of you who don’t know, what happens is the JITer, the compiler comes along goes:

You’re not using those methods and those types. So I’m gonna re-compile newtonsoft.json and just not include those things.

So then you get a smaller binary, which just has deserialise objects of type T, which is fantastic.

And then that also means, if it wants to, it can optimise that code, if it hasn’t already optimised .Because that’s one of things that .NET Core 2.2, I think, can do.

How Does It All Work?

It’s all CSHTML, so you downloading the razor files into the browser, except the razor files are all compiled into dlls - I’ll come into that in a minute.

So with ASP.NET and ASP.NET Core, in debug mod you can make a change to your cshtml, hit save, refresh your change is there. Fantastic. In Blazor that doesn’t work because you make a change, you save, then you need to re-compile the entire app because you’re sending dlls down to the browser, you’re not sending the HTML. So it all gets a bit wobbly.

But it is essentially these three things, right:

You’ve got components, which is very similar to angular or React components. It’s stuff that looks like HTML but isn’t, which is really cool. Each component can have a number of parameters or a number of things are injectable, and each component can have as many child items as you want. Obviously, the more you include, you get past the 20 or 30 limit will, it start slowing down the page render time, because it takes time to re-render.

Like I say, it’s along the same lines is angular and React, but it’s in .NET o it’s a more familiar to some of us who are more backend focused. And because it’s not angular or React, it’s really fast; but is a little big.

During one of the ASP.NET Community standups - they take live questions from the audience, so you feel watching on YouTube, I watch it on my phone, but if you’re watching on your computer, tablet, or whatever you’re watching a long with, you can actually post a question into the chat, and someone on the video feed will read out the question and answer it for you. But yeah, at about 22 minutes and 47 seconds into one of the ASP.NET Community stand ups, I asked a question, and that was:

Hey, these components look a little bit like razor pages. Are they the same?

So that way that it works is that razor Razor Pages is just CSHTML, it gets a little bit of pre-rendering done to it to create HTML and sends it down. But with Blazor components, it gets converted into a class on, then packaged into a dll, and set down to your browser - so that means that obviously, it’s no longer a mark up in the same sense.

So the Blazor runtime gets all of these dlls and you say, “Hey, give me this page,” and the Blazor runtime goes into these dlls and goes, “Right, I need to render this component here and that component there,” and it builds a fake render tree inside of your browser, in memory space, and that it takes that render tree, and that puts that on the screen. If you have multiple tabs on screen and you click the second tab, instead of having to redraw the entire tab it just goes, “right, we’ll just swap that component and out for this component,” and it just swaps things around so you’ve got a single page application without the crazy rooting, and the #!, and all that kind of stuff.

So there’s two types, and I’ll come on so that a minute, but you can have server side rendering where everything’s done entirely on the server, and the server goes, “Just update those five pixels for me,” and the browser just sits there as completely dumb terminal and goes, “okay,” shows you a pie chart or shows you an image. I don’t have any server side specific demos, but they’re not that difficult to make.

So rendering, it creates a Virtual DOM or a render tree and then inserts all of those components into that, generates the HTML from those components, and then displays that on screen. So this is clients only, but you have server side as well. I kind of hinted that.

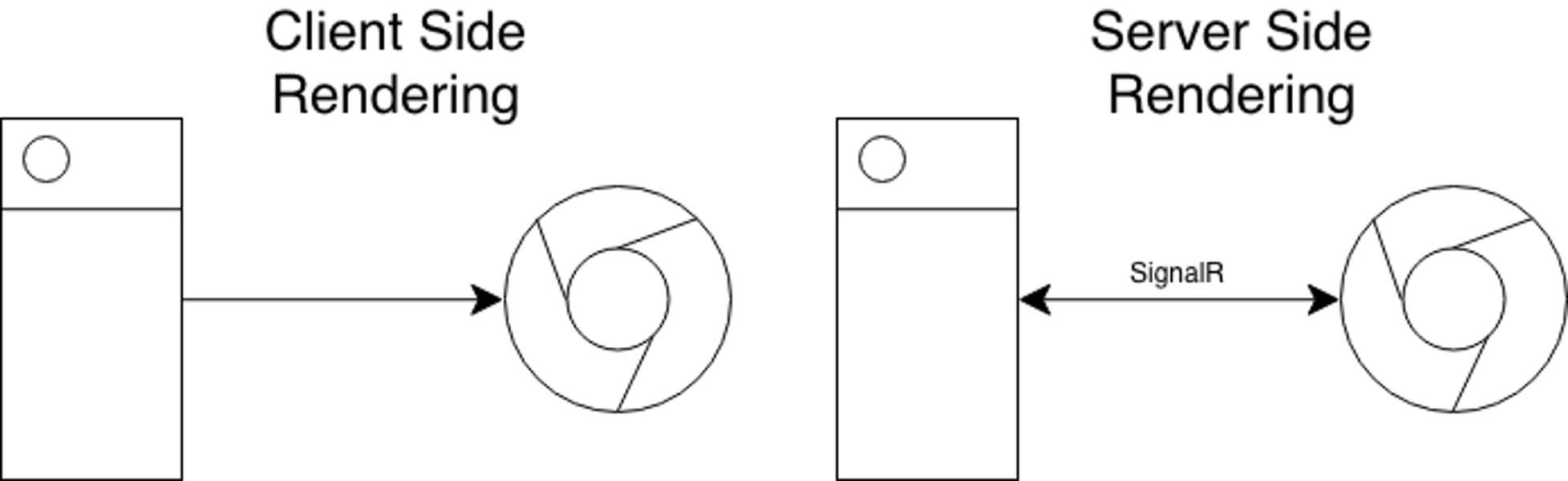

So there’s the two versions.

So on the left hand side of this image, so this is client side rendering. You’ve got the server, which is a wonderful image. You’ve got, say Chrome, client side rendering is everything is shifted to the client, and the Blazor runtime fires, and all of the things get loaded, and everything happens in the browser.

Whereas server side rendering what happens is the client says to the server, “can I ahve the page?” And the server goes, “Here’s a tiny bit of HTML, tiny bit JavaScript, CSS. The JavaScript sets up a SignalR connection back to the server, all of the Blazor stuff is done server side, and you’ve got this real time bi-directional communication between the browser and the server. Such that you could have, maybe, an analytics dashboard that lives entirely on the server on as thes messages come through, and you need to update your charts, a bit like the Azure dashboard. But the Azure dashbaord doesn’t use Blazor, but imagine the Azure dashboard, with the pie charts and bar graphs, and that kind of thing showing how your apps are living: imagine you had that. But that all the data was being piped, in real time, down to the browser. Because all that needs to happen is the server goes, “oh brilliant. I can run this at full time, change these charts, and just send down the pixels that need to be changed,” and that’s all that happens.

What Is Blazor Good For?

Blazor is really good at single page applications. If you need to just throw up a thing and have somebody interact with it, and get data back, it’s really good for that. Not so good for multi page applications because it gets a bit wobbly, and you have to map everything. But it’s really good, if you already have an API, it’s fantastic for adding a frontend to that.

And it’s really good for agile stuff, so if you need to build something really rapidly, Blazor is fantastic. Rather than having to pull down five million NPM packages, and then deal with, “this one’s not been updated, that one’s not been updated. I now have a vulnerabilities all over here.” Blazor doesn’t have that because it’s .NET. There are vulnerabilities with .NET, but they get fixed very quickly. I am actually attempting to build an entire blogging engine out of it, using markdown. So one of my blogs is entirely a markdown, I’m just try to build a separate frontend for that to see how fast it is. So I’ve got a blog that’s WordPress and one that’s Ghost - so that’s a JS frontend. I’m just trying to see whether, WordPress, Ghost, and Blazor: Which one’s fastest? Which one’s more secure?

There’s also Bletris - now, this isn’t one that I’ve written - which is Blazor Tetris. This one was announced a couple of weeks back. I couldn’t get this to work on my browser when I was trying this the other day, but essentially you’ve got Tetris being played in the browser. That’s a little C# code, that’s running there. That’s pretty cool. You could do whatever you can make video games, whatever you want.

So there are a few pitfalls with Blazor and I’ve mentioned a few already, these are things like:

- If you change the view, you need to re-compile the entire app because it gets compiled into your dlls

- Your .NET code is running inside of WebAssembly, which is running inside of JavaScript. So when it throws an exception, you’ve got 15 layers before hits you. So you get these wonderful stack traces that have 5,000,000 lines in them, and they’re all minified. Then you finally get to, “oh right, I got a null ref, but I’ve got 25,000 lines of exceptions, and then he gets to me,” which is a bit mad.

- It has experimental client side debugging. Oh, yeah, When these exceptions were thrown, your app continues running is not like C# where an exception happens and the whole thing stops. Your app keeps running because, “well I’ve already thrown that exception and I’m still sort of operating,” which is a bit weird.

What’s Great About Blazor

What’s greeat about Blazor is I have a shared dll here with one model in it, and it is my data model. This is a dll that I could run on a desktop, I can run on ASP.NET Framework, I can run in .NET Core, Mono, Xamarin, whatever I want, right? This is one dll and I don’t have to do any more TypeScript or JavaScript to C# mapping or anything, because this dll here is actually referenced in my page there when I did fetch timeline. I’ve actually got an actual use of that dll. So I’m pulling the dll through. So I no longer have to keep all of my view models and my data models in sync, because it’s the same model.

So at works we’ve got a project you give it a bunch of C# models and it will produce the TypeScript models. The problem is, you’ve gotta remember to keep running that script to keep them up to date - maybe you could do on a build or something - but you’ve got to remember to do that. Whereas this is the actual models. If I scroll down here here, I’m actually saying, “go get me an array of these items,” which is fantastic because I don’t have to do anything special.

// Controller side - runs in the browser

[HttpGet("[action]")]

public async Task<IActionResult> GetTimeline()

{

var headlessClient = Authenticate();

var timelineItems = await headlessClient.GetAll<TimelineItem>();

return Ok(timelineItems);

}

// client side - also runs in the browser

@functions {

bool loading = false;

TimelineItem[] timeline;

private async Task LoadTimeLine()

{

loading = true;

timeline = await Http.GetJsonAsync<TimelineItem[]>("api/SampleData/GetTimeline");

loading = false;

}

}It’s not the best code ever, because I threw it together like two or three days ago. So again, passing in that parameter, this POCO, I’m passing it all the way down. But it’s C# is running in the browser, right?

So the one thing I don’t like about this is in Umbraco I’ve got that text field, which is a markdown field; it renders it on the headless Umbraco end, then sends me the HTML down the pipe. If I go back to this view, where’s my view, over here. I’ve typed in a couple of hashes and a bullet point there, that gets converted to HTML and then sent down the pipe.

// view component which renders the TimeLineItem

@using Microsoft.AspNetCore

@using UmBlazor.Shared.Models

<div class="timeline-item">

<div class="time">@Item.Date.ToShortDateString()</div>

@((MarkupString)Item.Description)

</div>

@functions {

[Parameter]

private TimelineItem Item { get; set; }

}If I don’t do MarkupString, it literally just puts the string there. So I’ll get <h3> then the text and then hyphen. So I’ve had to pull in ASP.NET Core into this view to be able to do that. If I can figure out a way of doing that without using MarkupString or HTML.Raw, this page will load infinitely faster because it’s not having to include ASP.NET Core. But because it’s doing IL Shaking, I’m saying include ASP.NET but it will actually only include the methods required to expose that API. So there’s this tiny thing that’s running in my browser.

So I’ve got a model and passing to Umbraco, the model I’m consuming on the server, and on a model I’m using the client, and they’re all exactly the same. I don’t need to say to Umbraco, “Okay, I’ll do a DTO to your format, and then a DTO back to my foramt, then another DTO over to the client.” It is literally just, “Here’s your C# and just pass it around,” which is mad.

There’s loads of documentation and examples on Blazor out there in the world. There’s the official docks, which is blazor.net; Ed Charbeneau of Progress Telerick a weekly twitch stream where he’s building some apps in Blazor on Blazor State Has Changed. I had Ed on episode five podcast.

So I’ll say, any questions? It says here that it’s been 42 minutes, but nobody’s coming to tell me to shut up. So if you have any questions, I can attempt to answer them.

[Question from the audience: What are the security implications of running a random dll in the browser?]

Right, yes. So that’s a really important question. So the question was, “What is the security implications of loading a random dll into the browser?” Well, what’s the security implications of loading a random NPM package into the browser?

Same sort of thing,right? Except you’ve got a similar sort of locked down, runtime, walled garden area. So you have the same idea. So how many of us use newtonsoft.json? Keep your hand up if you looked into the source code. You’re loading this random dll in, and you’re assuming is good because it’s part of the .NET Standard, so you assume that it’s good.

Yeah, you’re right: loading a random dll into the browser can be dangerous. Again, it’s up to you to sort of vet that. In the same way that there was the talk, this morning, about the security stuff, you kind of need to vet the code that you’re going to run anyway.

[Question from the audience: I was wondering what the current browser support is, and the operating systems?]

Okay, so it’s essentially: If you can run WebAssembly, you could run Blazor. So if you search on Can I Use for Web assembly, you can see that browser support essentially for WebAssembly is the same as

[Question from the audience: There’s no dependency on anything .NET?]

No dependency on .NET because as long as you can run WebAssembly, you can load the version of Mono that’s compiled for it. So as long as it’s one of those green browsers along there, i.e. nothing made by Microsoft - well, I mean, Edge works, but “works” - but as long as this one of those green browsers there, then it will work. So there is a shim available for IE11, I believe.

I think that’s all I’ve really got to see about Blazor. But if you have any other questions, I can totally the answer them. If you want to talk .NET Core, I can talk .NET Core. If you want to be on the podcast let me know as well. If you want to sticker, if you figured out what:

Part one: In which Doris gets her oats

is, come and let me know and I’ll give you a sticker or just let me know and you don’t have to have a sticker.

Thank you all so much.

Wrapping Up

This episode was an edited version of the talk that I gave at Umbraco Festival 2018 on Blazor. Check out the show notes for a link to the full video version of the talk, which The CogWorks have graciously allowed me to use for this episode. So my thanks go to them for allowing me to use the audio, and for running the Umbraco Festival and allowing me to talk there.

Remember to check the show notes for a link to the full transcription of this episode, which is available at dotnetcore.show. Also, don’t forget to join the mailing list or the Slack group for the show - check the show notes for a link.

And don’t forget to spread the word, leave a rating or review on your podcatcher of choice, and to come back next time for more .NET Core goodness.

I will see you again real soon. See you later folks.

Useful Links

- Sign up for the mailing list

- Join the Slack group

- @dotnetcoreblog

- the slides for this talk are available on GitHub

- the SpaceJam website

- nodejs on a satellite

- WebAssembly

- Web Apps can’t really do that, can they? - Steve Sanderson

- Paul Seal

- ASP.NET Core Community standup

- global assembly cache

- Bletris

- blazor.net

- Blazor State Has Changed

- Ed Charbeneau was on episode five of the podcast, talking about Blazor

- Can I Use for Web assembly

- Blazor.Polyfill