Episode 10 - Configuration in .NET Core

Embedded Player

The Modern .NET Show

Episode 10 - Configuration in .NET Core

Supporting The Show

If this episode was interesting or useful to you, please consider supporting the show with one of the above options.

Episode Transcription

Hello everyone and welcome to THE .NET Core podcast - the only podcast which is devoted to:

- .NET Core

- ASP.NET Core

- EF Core

- SignalR

- and not forgetting The .NET Core community, itself

I am your host, Jamie “GaProgMan” Taylor, and this is episode 10: Configuration in .NET Core. In this episode, I’ll take you through just how you can configure your .NET Core and ASP.NET Core applications using the new appsettings files.

So lets sit back, open up a terminal, type dotnet new podcast and let the show begin

Introduction

Cast your mind back to the days of ASP.NET development (which isn’t that far back for most of us), and think of the ways to pass application settings into your web app. Essentially we had web.config,which was an XML formatted text file with all of our config stuff in it.

Usually it started out quite small, with maybe about 20 to 30 lines in it. You’d need to add a database connection string, so that added three lines. Then there were the HTTP headers and System.Web specific config. Then you’d have some app settings like external api keys or urls. Before you knew it, you had a massive web.config file.

Then you’d have to transform it for your different environments. Usually you’d have a transform for UAT, and one for Live. You’d have to tell your build pipeline to transform the config for the relevant environment.

For those who don’t know a web.config transform was a subset of the web.config, each node having a set of attributes applied to it to tell the build system what to swap out and where.

But what if you wanted to hide some of the details in the web.config? After all, it was a plain text file on your server, and anyone with access to the server also had access to your web applications config - although, if some malicious actor has access to your server then you have bigger problems.

Reading values from the web.config was fraught with danger, too. You accessed it like it was a dictionary, and if your key name was wrong, you’d get null. That’s right, you’d either get a string value or a null, which meant that you then had to check and cast the value before you could use it.

.NET Core seek to make this simpler.

appsettings.json

That’s where appsettings.json comes in.

…or appsettings.xml, or appsettings.ini if you prefer.

If you’ve used ASP.NET Core then you’ve already seen this in action in one of two ways.

If you’ve used ASP.NET Core 2 or later, then in your Program.cs file, you’ll have called CreateDefaultBuilder. This method essentially bootstraps a lot of the code required to set up Kestrel, including loading the contents of a file called appsettings.json.

However, if you’ve only used ASP.NET Core 1 then you will have spotted code in your Startup class which does the same thing.

Both paths eventually run the same code, which is similar to the following:

var builder = new ConfigurationBuilder()

.SetBasePath(env.ContentRootPath)

.AddJsonFile("appsettings.json", optional: true, reloadOnChange: true)

.AddJsonFile($"appsettings.{env.EnvironmentName}.json", optional: true)

.AddEnvironmentVariables();

Configuration = builder.Build();(check the show notes for the code, I’m not going to read it out to you)

If you’re using ASP.NET Core 2.0 or above, then you’ll have to go to the declaration of the extension method CreateDefaultBuilder found in the WebHost class.

Essentially what this code does is it looks in the directory where the compiled version of your app is started from (i.e. the location of your app.dll or similar) and loads any files with the name appsettings.json into memory.

You can think of the appsettings.json file as being ASP.NET Core’s web.config, with the added bonuses of the file being much simpler and it being in JSON.

I think that we can all agree that JSON is much more human friendly than XML

The typical things that you’ll find in the appsettings.json for a newly created ASP.NET Core project are:

- the logging level to use

- the database connection string

- CORS policies

- etc.

appsettings Inheritance

If you take a look in the repo for an ASP.NET Core application, you’re likely to find multiple appsettings.json files. Most often, you’ll find:

- appsettings.json

- appsettings.Development.json

- appsettings.Production.json

All three of these files can be used by ASP.NET Core’s ConfigurationBuilder, which we saw earlier on.

unless you haven’t checked out the show notes yet, that is

When we called the ConfigurationBuilder’s AddJsonFile method, we passed in a variable called env.EnvironmentName. The env variable is an instance of the IHostingEnvironment variable which is added (via reflection) for us by ASP.NET Core and represents the hosting environment for the running application.

When you run a .NET Core application, either by issuing the dotnet run command at the command line or via one of the Visual Studios or Rider (or similar), you implicitly set the hosting environment. If you don’t supply it (I’ll tell you how in a moment), then .NET Core assumes that you are running in production.

The reason for this makes sense when you think about it: how can the runtime know, at boot-time, whether your application is running on a dev machine or on a production server? So it’s programmed to hedge it’s bets and play it safe.

You can override this by prepending the call to dotnet run with ASPNETCORE_ENVIRONMENT=Development or by altering the launchSettings.json file. This file can be found in the Properties directory of your source code and contains information on how the .NET Core runtime can boot your application. The most important part of this file, for our current discussion, is the ASPNETCORE_ENVIRONMENT variable.

Usually, this will be set to Development and this is the value that the runtime will use, if the file is present. If it’s not, then it will fall back on a global entry. And if that’s not present, then it will use Production.

All of this is giving hints on how application settings are handled, by the way

When you application boots, it will load the appsettings.json file as your application config. Then it will look for an appsettings.{environment}.json file (where {environment} matches the environment that the application booted in), if it can find the file then it wil load it and replace any key:value pairs that are already in your application config with those found in the file it just loaded for your environment.

Which is a round about way of saying that the values in appsettings.Development.json (for example) overwrite any values from appsettings.json.

I’ve focussed on json files here, but you could just as easily use xml or ini files.

What About Secrets?

Let’s say that you don’t want to expose your database connection string to the outside world. In fact, that’s one of the things that I pointed out in a blog post all about User Secrets back in September of 2017.

check the show notes for a link

.NET Core has a wonderful feature called “User Secrets”, which is an extension of the appsettings.json. Essentially the idea is that you don’t want to commit secrets (such as connection strings, api keys, and passwords) into source control.

Ever.

One of the ways you can stop that from happening is to have these secrets loaded in from a file external to your binary. And I don’t just mean the appsettings.json here, I mean fully external to your application.

The way this works in .NET Core is to load a json file from the user’s home directory rather than from the source or binary directory.

If you are on Windows, this file will be found at: %APPDATA%\Microsoft\UserSecrets\<user_secrets_id>\secrets.json, whereas MacOS or Linux users will find it at: ~/.microsoft/usersecrets/<user_secrets_id>/secrets.json

The important thing in both of those directory paths is the <user_secrets_id> part. This is a GUID which is taken from your csproj. An example would be:

<Project Sdk="Microsoft.NET.Sdk.Web">

<PropertyGroup>

<UserSecretsId>c86e8433-1aae-4540-b84e-d5121dc2a0cb</UserSecretsId>

</PropertyGroup>

</Project>As long as your csproj has a UserSecretsId element, then you can use the CLI to add a secret. The format for the command is: dotnet user-secrets set "key" "value".

So let’s say that you wanted to set the connection string to be “./mydatabase.db”, that would be dotnet user-secrets set "connectionString" "./mydatabase.db"

If you are in Visual Studio, you can right-click on the Solution and choose “Manage User Secrets” which will open a json file for you to store all of your secrets in. That json file will be stored in that user secrets area. If you hadn’t already given your app a User Secrets id, then Visual studio will generate one for you.

Just like how the values read from the appsettings.json file are overwritten by those read from the appsettings.{environment}.json file, any values found in User Secrets will overwrite the values found in appsettings.{environment}.json

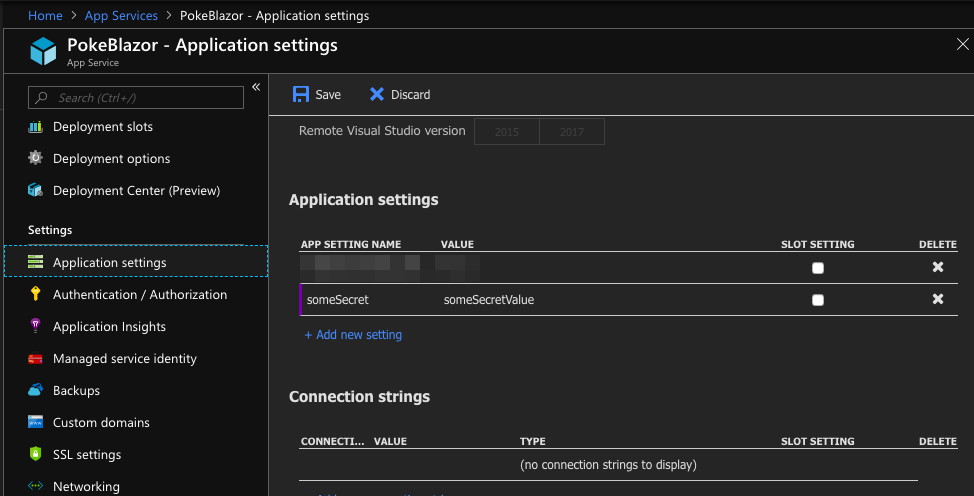

But what about Azure?

Let’s say that you’ve created your app, used appsettings files and User Secrets for all of your environments, but you want your Azure app instances to have the same functionality.

Well once you’ve uploaded your app to Azure, you can set secrets on the Properties pane of your web application. These work in exactly the same way as User Secrets, except that they are loaded in last so will be used to overwrite values last.

Using The AppSettings Values

This is where the extremely clever bit comes in: .NET Core will actually read your appsettings.json file into a POCO of your choice (as long as it adheres to the json, that is), and you can inject this POCO into any controller using standard constructor based dependency injection.

public class MyClass

{

private readonly AppSettingsPoCo _appSettings{ get; set; }

public MyClass(IOptions<AppSettingsPoCo> appsettings)

{

_appSettings = appsettings.Value;

}

}see the show notes for a short code snippet on how to do this

Wrapping Up

In this short episode, I’ve talked a little about how the appsettings.json (xml or ini) are loaded, how you can override them with environment specific versions, and how you can use User Secrets and Azure to override them at runtime, too.

Hopefully you’ve found this interesting, if you did then let me know by sending me a tweet @dotnetcoreblog, or head over to the website dotnetcore.show and let me know what you think.

Remember to check the show notes for a link to the full transcription of this episode which also has links to a bunch of related websites and resources. These is available at dotnetcore.show.

And don’t forget to spread the word, leave a rating or review on your podcatcher of choice, and to come back next time for more .NET Core goodness.

I will see you again real soon. See you later folks.

Useful Links

-

YouTube version of this episode

- The YouTube version of this episode, if you’d prefer to listen there

-

Multiple Environments in ASP.NET Core

- From the Microsoft docs

-

IHostingEnvironment

- Also from the Microsoft Docs

-

Managing User Secrets

- More Microsoft docs

-

appsettings.json - A Short Discussion

- A YouTube video that I created to show off appsettings.json in a more visual way

-

User Secrets

- A blog post that I wrote on User Secrets in September of 2017

- It includes some interesting stats on the number of GitHub commits for “Remove Password”, “Remove apikey”, and “Remove connection string”

-

ASP.NET Core 2.0 Configuration and Razor Pages

- A blog post of mine from May 2017 about appsettings.json