Episode 56 - Debugging in Production with Omer Raviv

Embedded Player

The .NET Core Podcast

Episode 56 - Debugging in Production with Omer Raviv

Supporting The Show

If this episode was interesting or useful to you, please consider supporting the show with one of the above options.

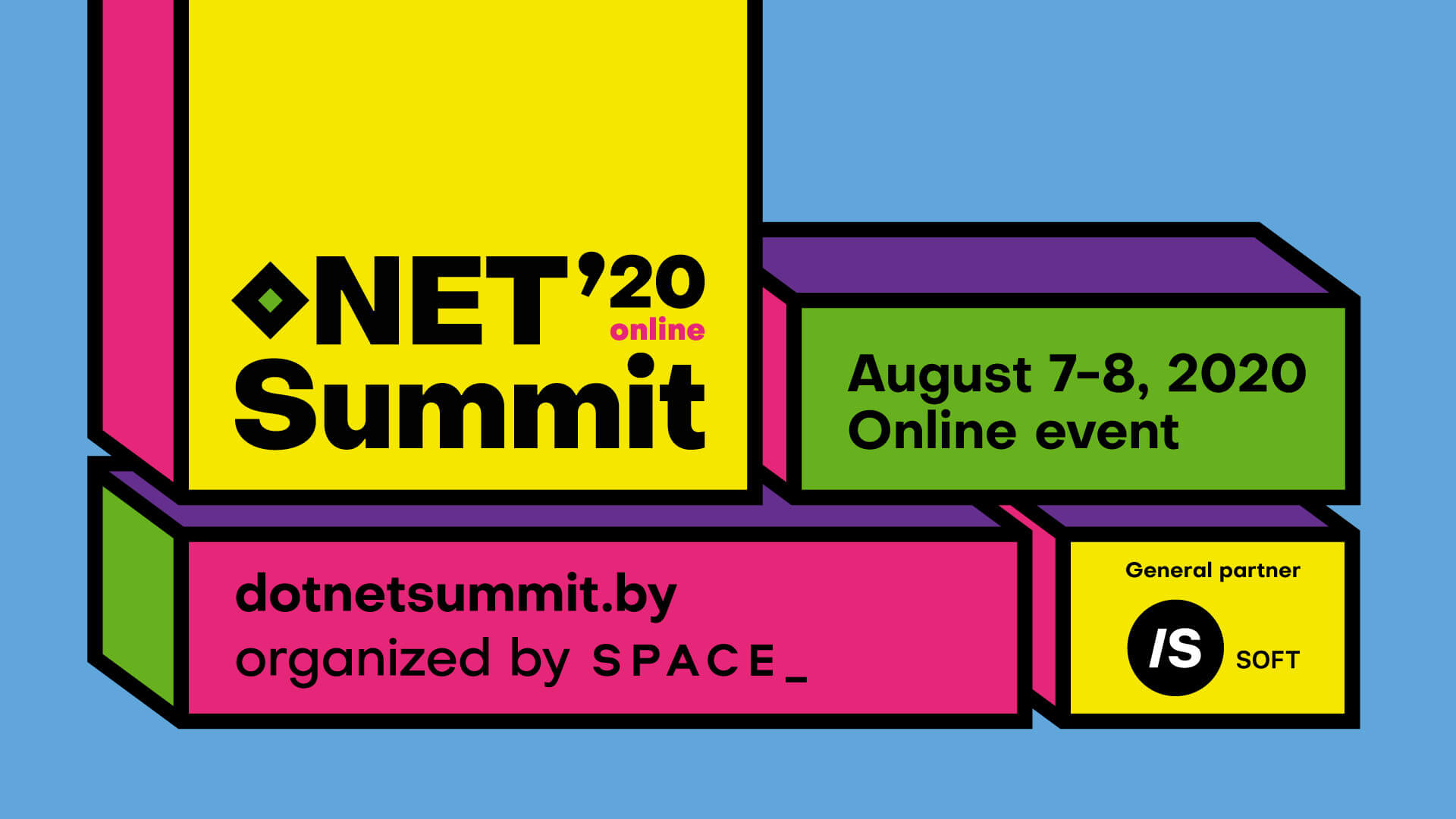

.NET Summit 2020

Have you heard about .NET Summit? .NET Summit 2020 will be held online on August 7 and 8 (3pm-7pm GMT+3). Speakers include podcast alumni Dylan Beattie and Alexey Golub. Check the website for .NET Summit for updates.

Regular tickets are on sale at 65 EUR - get yours before price increases on July 28 - at

https://dotnetsummit.by/#tickets. Listeners of the podcast can get a 15% discount by using the discount code DOTNETCORESHOW15 at checkout.

.NET Summit 2020

Episode Transcription

Sponsor Message

This episode is sponsored by ConfigCat

- Are you looking for a service to support dynamic feature toggles?

- ConfigCat is the feature toggle service for teams.

- It is cross-platform, trainable in 10 minutes or less, and it’s the same price regardless of team size.

Check out

ConfigCat and get 50% off any paid plan with code NETCORESHOW or just use ConfigCat’s generous free tier.

Hello everyone and welcome to THE .NET Core podcast - the only podcast which is devoted to:

- .NET Core

- ASP.NET Core

- EF Core

- SignalR

and not forgetting The .NET Core community, itself.

I am your host, Jamie “GaProgMan” Taylor, and this is Episode 56: Debugging in Production With Omer Raviv. In this episode I interviewed Omer about debugging .NET Core applications, the tricky subject of debugging in production, and a new product that Ozcode have created which aims to make debugging easier to do.

So let’s sit back, open up a terminal, type in dotnet new podcast and let the show begin.

The following is a machine transcription, as such there may be subtle errors. If you would like to help to fix this transcription, please see this GitHub repository

Jamie

First thing I want to say Omer is thank you ever so much for spending some time with me. I know there’s a considerable time difference between yourself and me. So I appreciate that it’s a lot later for you than it is for me right now. So thank you ever so much.

Omer

Absolutely. Pleasure to be here.

Jamie

It’s a pleasure to have you on the show. It’s a pleasure to always have someone on the show because otherwise, it’s just me talking, and I’m sure that I can get put away for in some kind of institute for just sitting and talking to myself, but that’s the one side. So, first thing I always like to ask people is for the folks who maybe don’t know too much about you and some of the work that you do, would you mind giving us a sort of brief introduction? Is that okay?

Omer

Absolutely. So hi, I’m Omer Raviv. I’m the creator and CTO of Oz-code. I’ve spent most of my career working on like being a fanatic around two topics, mostly all around software quality, but specifically around the debugging, debuggers, testing and how do we, as developers, you know, just become more efficient at solving difficult bugs.

And that sort of started for me at my very first job as a software engineer. I was you know, working as a as a junior developer in medical imaging. So I was working on the software that the doctors and the technicians at the hospital all used to operate a CT scanner, and every few months used to actually take us out to the hospital to actually see how our code is being put to use and, and that’s sort of where my, my professional career began. Just like very nervous moments of like, being in the actual X ray room staring at the computer screen and just thinking to myself, “you know, I really, really hope this thing doesn’t crash, because if it does, then, you know,” then they have to deliver a double dosage of radiation that’s laying on that bed over there. They’re probably gonna want a better answer than just “null reference was not set to an instance of a variable,” right. So that was sort of the catalyst for me to pursue, “how can we make debuggers work for us rather than us working for the debuggers?”

Jamie

There’s a lot to unpack there. And there’s one thing I do want to bring up. And it’s, I was talking to Dylan Beattie - who is the creator of the Rockstar programming language - not so long back. By the time this goes, I will be long back. Earlier this year, I was talking to him at NDC, London. And we were talking about a number of times where software testing has maybe not been up to scratch. And we talked about a medical radiation machine that in a similar sort of way, it a screen you could type in, “10 micrograms of radiation,” or whatever. And if you hit backspace, it would remove the previous character from the screen, but not from memory. So sometimes people got 10, one hundred, a thousand times too much. And that’s just a UX thing. That’s not the software. I mean, the software was broken but not like a null ref. So code around medical devices, scares me. If I’m honest, I wouldn’t want to be in that position. Not that I don’t trust myself to write bug free code, because no one can write bug free code. But it’s that, “if I get this wrong someone could be really, really harmed.”

And it’s interesting, you brought it up because I recently finished re-reading The Pragmatic Programmer, the 20th anniversary of it.

Omer

That’s a fantastic book.

Jamie

It really is. And one of the tips towards the end of the book is, “do no harm.” As developers, whatever we’re working on - whether it is medical imagery, whether it’s a video game, whether it’s some kind of business line application, whether is literally just a CRUD application, whether it’s some kind of e-commerce site - we all have that ability to somehow harm our users. Whether it’s fiscal harm by messing up and charging them too much or some kind of physical harm. Another example that Dylan brought up was in the UK at least, if you want to become a lawyer, you have to go through a very specific set of, I want to say, set of steps. And one of those steps is applying for internships and things like that. But because of various things relating to the way that the UK law system was set up, you have to do it at a very specific time frame. And there’s only like two or three hours or two or three days when you can do this. And you have to use one very specific web app to do it. And the web app isn’t really that well put together. And there are stories of people who are: it’s two or three o’clock in the morning, and they start able to submit their documents and if they miss this window, they’ll never become a lawyer. So like someone’s code is causing someone to cry at two o’clock in the morning.

Omer

Yes, as developers, we make people cry. That happens. People are deeply affected by software and it can be anywhere from a frustration to also a huge monetary loss, right if you if you think about some of the scariest issues that have made it to production, there are literal billion dollar mistakes that have been made and million dollar mistakes. Because if a bug makes it into production, it’s no longer just a matter of, you know, time that the organisation has, you know, wasted chasing that bug. It’s the actual loss of reputation. And the fact that most people nowadays with our short attention spans will, if a web app doesn’t work, they’ll immediately move on with their lives, they won’t send you an email that saying, “Dear sir, here are the exact steps to reproduce the issue that I had on your on your site,” they will just say, “eh,” and then they’ll go use somebody else’s site for sure.

Jamie

Some family and friends have made fun of me. Because I will literally say, kind of throw my hands in the air and say, “no, I do not have time in my life for badly written software.” And I will just literally move on, which is an exact, I think, pretty much an example of what you’d said there. If I’m relying on a piece of software to do something for me or to help me do something. And it’s badly written and it falls over with what I believe is the happy path I just give up straight away. “No, I can’t do this, I’m going to go use something else,” like you said. And then that means that maybe that company’s bottom line is directly affected because I’m not providing business to them, or they’re not providing value to me. And yeah, you’re absolutely right.

Omer

Yeah, absolutely. I think that in a sense, it’s a blessing that our children have an even worse attention span than us because that means that they’re even less accepting of bad software than we are as adults. They’re like, “nope, this doesn’t work. Move on to the next thing.” And that’s good. We should have extremely short tolerance of bad software because our world is starting to run increasingly more and more on software. So this notion of software quality, how can you know, the people who are making software, make sure that it’s good that it answered the needs of the customers that it doesn’t crash; that it’s up all the time and rather than being down, whatever percentage of the time. It’s good to have the bar go increasingly higher with every year. I think that’s a very big sign of maturity for the software industry, which to me, I, as a member of the software industry, I still feel like I’m just glueing together these, you know, paper mache pieces. So it’s good that we’re doing it in a good vector. That’s what I think.

Jamie

When I started learning to program, I was kind of a late entry to programming properly. I used to do it in a bedroom coding and stuff. But when I got to college - so in the UK, college usually starts at around age 16. So you finished high school around 16. And then you’ll go on to college in the new university. And at college, my my lecturer said, “programming is kind of like Lego or any kind of other construction blocks, right? You’ve got a whole bunch of things that you just kind of glue together;. By you glueing them together in the correct way, you create the application.” And I think you’re right, I think at the moment, we’re not actually using the Lego blocks. We are indeed using paper mache at the moment and over time, we’ll be able to bake that into clay and then into plastic. And then hopefully, we’ll get to the point where it’s steel, or some other metal metaphor, because then it will be sturdy. But yeah, at the moment, not so much. But then there are millions of programmers and we’re all working together on this thing. So we will get there. Right.

And I think it’s important to say as well that, you know, bad software. Like you said, the average user may just go. “no, I’m done and move on.” But I read a story not so long back about in the Windows world we had the Y2K problem; in the Unix world - so Linux, Mac OS, BSD, those kinds of things - we have this problem called the 2038 problem, which is taking a 10,000 foot view of it: When Unix was first released, the time was recorded in seconds since the midnight of January 1st, 1970. And we are very rapidly coming up to the end of that 32 bit integer. When that takes over, it will go back to zero and everything will think it’s 1979 again, which is not good. There’s a big push to solve this issue. But the problem is that, because a lot of the banking and finance industry uses old software running on Unix boxes from the 70s and 80s, it isn’t as easy to upgrade and replace that 32 bit integer with a 64 bit integer. And we’re already starting to see the problem manifest itself because there are companies who will need to plan 20, 30 years in advance. And we’re recording this and 2020, so 20 years from now is into 2040 after the 2038 year problem. So there are companies who are losing money every day because their calculations for say mortgage repayments are coming back as negative because it is no longer, the way that they working out the percentages, is now become a negative percentage for 2038 2039 2040. Because the computer thinks it’s 1970.

Omer

Yeah, absolutely. And I think this all comes back to the this is something that we as developers aren’t really that conscientious of, or conscious of as we go through our day to day is just that: software bugs cost money, they cost a lot of money. And that cost is like directly proportional to how far away from our fingertips the bug was actually discovered, right? Because it’s very common fact in computer science research that if I, as developer write a bug, and then discover it, you know, in a few hours after I wrote it while I’m just debugging my own code: okay, that has a certain cost. But then if the QA engineer finds the bug that has a several orders of magnitude higher cost, because, you know, the QA engineer has to go in and write a bug report and that takes time to write a good bug report. And then I have to read the bug report, try and reproduce and then say, “nope, it absolutely works on my machine,” and then mark it as not a real bug. And then we have to arm wrestle to figure out what is real bug or not, and eventually maybe they’ll prove to me that it is indeed a real bug. And I’ll have to struggle even more to reproduce it and then fix it.

But of course, if it’s found in production that has several orders of magnitude, higher cost as well, because obviously, if something made it into production, probably it’s very, very specific to that particular users use case hopefully, we probably should have, hopefully, maybe caught it with automated testing earlier on. But this particular bug was super, super specific. And, of course, again, there’s this notion of the loss of reputation, not just the loss of business value.

Jamie

Sure. I don’t know, I feel like whilst the software that we write and the tools that we use have become more complex, for good reasons, because you know, it’s useful, let’s say with .NET, to be able to, my friend James calls it pretend programming, right. Because there’s all of these components that are really high level. You don’t have to read an HTTP Client, you don’t have to write a JSON deserialiser, you don’t have to write memory management. You just glue it all together, write your little bit, which I say “little bit,” might be millions of lines of code. But you also don’t have to write the billions of lines of code required to talk to the operating system, to talk to the network card, to talk to the hard drive, that kind of thing. So we’re getting a little bit further and further away from the hardware. But that makes things a little easier.

But then I also think that because we are at - I’m going to play a little bit of buzzword bingo here - because we’re at a point where we have things like DevOps and continuous integration and continuous deployment. It’s very easy to go, “meh we’ll fix it if the user finds it,” click Deploy. We’ll get on to it in a couple of minutes. But debugging in production is hard. Debugging locally: easy breakpoint. Right, I can see it, but in production, almost impossible.

Omer

Yeah. And I think that the shift to DevOps, I really like to quote the staff from the Puppet state of DevOps report that they do every year. So I think a couple years back, they showed this graph which shows very, very visibly, that we’re seeing a trend as an industry right now that we are indeed moving fast and breaking more things, right? The amount of deployments per year is rising. And the meantime to recover is rising as well. And I think that there are several reasons for this, like the answer to, “why is this happening?” Is kind of complex, I think part of it is just the fact that we are indeed under it, the large you know, demand to release more software, more releases, more deployments, more quickly. And we don’t have good enough tooling to figure out whether these new deployments are faulty or not.

But I think another big part of it that came with that is just a move to a more cloud native style of development. Because today, you know, when I, as a developer, you know, write a line of code, it’s very short interval of time between that moment that I write the line of code until I actually need to see it running in a Docker container out there somewhere in the cloud, where I do don’t really have access to it. And typically the software that we write today’s usually, you know, user clicks a button on their web app or mobile app, and then that goes through microservice A to microservice B to microservice C. And finally, an exception is thrown on microservice D, and how do I even piece together that chain of causality that led up to that particular failure? That’s a really hard problem to solve.

Jamie

Yeah, absolutely. And it’s a difficult one, because unless you have something like, as little as just logging everything, but then if you log everything and get then get a billion users, harddrive space is not infinite, you know.

Omer

Absolutely. And as a way, in a way I feel like because logging, as you mentioned, is kind of like the only tool in our toolbox right now to deal with actual debugging and troubleshooting of code that’s deployed to the cloud. We were sort of regressed as an industry we like to sort of put lipstick on a pig and call it observability. But I just call it printf debugging, right. We’re going through this very, very tedious process where, you know, we try and log everything, which of course creates a huge amount of logging information. Like I’ve seen systems doing consulting, that like 90% of the resources of the cloud services is just crude chunking out these huge amounts of logging, and then, you know, sending them. And then of course, we have to pay considerable amounts of money to tools like you know, logz.io and spunk, and all those cool companies that you know, are able to handle such vast amounts of information.

But then I think another big problem with using logging as a tool for actual debugging and troubleshooting is just that your feedback loop is way too slow, right? Because typically, what happens is that you know, something bad happens. You get either an exception, call stack from whatever monitoring tool or APM that you’re using, or you just get a very angry from phone call. And then you look at the logs, which is, first of all, a needle in a haystack problem. But if you’re doing microservices, you have now several needles that you need to extract from several different stacks of hay. And then typically what happens is that you figure out there actually isn’t, despite your best efforts, there isn’t enough information in the logs to actually figure out the root cause of the bug. And which kind of makes sense because there’s sort of like a hidden paradox there. Right? “If I had known in advance what logs I’m going to need, I probably just wouldn’t have made the bug in the first place,” right? So we go through several iterations of this adding more logging, and then re-deploying the application, going through the entire CI/CD pipeline, then getting the new logs, maybe doing that several times until we actually understand the problem and can hopefully, maybe try to reproduce it or at least guesstimate the root cause and fix it and continuously monitoring production to make try and make sure that we actually fix the problem.

And that’s a very sad story because, as developers, we’re kind of, you know, we need to have this short feedback loop we’re used to like, “okay, I’m going to compile it; I’m going to run it; I’m going to debug it; doesn’t work,” and cloud native type of development has sort of taken that away from us.

Jamie

I guess now might be a good time to sort of intro your your company’s product right? So we connected over Twitter, because you were telling me about a production debugger that hopefully will help to - I don’t want to say “solve” this problem because I don’t want to set people up for, “wow! I just installed the thing and I’ll never have any bugs,” to make it easier to track them down I guess is the probably the correct way. I mean, why don’t you tell us a little bit about it because I’m gonna get it wrong and then people would be like, “but Jamie said it was awesome.”

Omer

So Oz-code, to continue on from sort of like the brief history of the the story of my life.

So after spending about a year and a half in that medical imaging company and being you know, very scared and very frustrate with the state of, you know, the Visual Studio debugger, I kept feeling like the debugger should do more to try and help me figure out the bugs. I kept spending these huge amounts of time dealing with very complicated problems that all had to do with the free box object that represented the space in the patient’s body that we’re going to be scanning. And, you know, we had to constantly flip it from one coordinate system to the other. And I kept getting it wrong and spending so many hours trying to debug it and just not being able to be successful at debugging. And I think that was sort of like the turning point for me, I came to this realisation that, again, getting back to this point about feedback loops, I kind of reached this realisation that the real challenge in debugging is really equal parts, intellectual and emotional in a way. Because when you’re debugging, you’re trying to solve the same problem for an hour, and then yet another hour, and yet another hour.

And to be successful at debugging, you have to like be very rigorously applying the scientific method, right. You need to form a hypothesis, to prove or disprove that hypothesis, then move on to the next hypothesis. But when you’re trying to solve for hours and hours and days, and sometimes even weeks, you tend to brush up with your own personal feeling of personal failure. And that is exactly the thing that, you know, turns you into a zombie debugger, turns you into a person that just staring blankly at a computer screens, hitting that step over button over and over, just sort of waiting for the bug to jump out of the computer screen and bite you hopefully.

So when I came to this realisation, I decided to leave. Oz-code code was born. So Oz-code’s first product is a Visual Studio extension that just makes debugging C# code in Visual Studio a lot more productive and fun. With things like debugging LinQ queries more efficiently visualising the code’s execution, making it easier to drill into collections and search and filter them etc, etc. But over the past two years, we’ve been more focused on our new product, which is the Production Debugger. And the production debugger is essentially a tool that you install an agent wherever your code is running. And that agent allows you to essentially debug your code in a non intrusive way, even when it’s already in the cloud deployed to your production, staging, or QA environment.

So one example of .NET Core application that’s running out in a Linux Docker container somewhere. Rather than doing the whole song and dance of trying to solve it using logging, as we described earlier, what happens when you have the Oz-code agent installed is that the first time the exception happens, Oz-code monitor analyses the code path that led up to that exception, and it turns on a lightweight code instrumentation along that path. And so the second time the exception happens, we actually give you a full fidelity time travel recording of line by line, “here’s what happened.” So essentially giving you the same amount of information that you would have gotten if you had somehow magically happened to be able to instantly reproduce the bug and put a breakpoint in Visual Studio and hit that immediately. We do that by giving you a web based debugging experience. So it’s just a link to you you know, enter personally or you can invite your colleagues to share and then you can collaborate and look at the same code execution on the same exact version of the source code that was in production at the time the bug happened. So that’s just one example of the ways that the Oz-code production debugger sort of turns this problem of dealing with production errors on its head.

Jamie

Oh right, I see. That’s always been one of my problems with debugging code that happens on production: If I get some kind of bug report, it says maybe the the old school yellow screen of death, right? the old .NET MVC, yellow screen of death, and it’s like, “line seven, this value.” And I’m like, “`brilliant. I’ll go and have a look at that. Oh the code has changed 14 times since it went to production.” I can’t debug it. Right I don’t know what I’m looking at because the production code is so far behind what I’m looking at. So then I’ve got to figure out, where’s that release? Where was it tagged in source control? Pull that version of the code. Right now I can get it up and running. Oh, I don’t know what was fed into it. I just know that it fell over. How can I get a null ref there? Yeah, I can, I can certainly see how that would be immediately useful. If I can just send a link to someone and go, “go check it out, you can actually see the value that they’ve given. You can see why it’s fallen over.”

Omer

Yeah, absolutely. Actually, that problem that you just referred to, there are now good solutions to that in the .NET Core world and the modern .NET Framework world; technologies like SourceLink. So for our listeners who may not be familiar, this problem of let’s say, you know, you have an exception stack trace or you even better you have a memory dump - because in .NET Core world we now have cool new tools that Microsoft has given us like [dotnet-dump](https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/dotnet/core/diagnostics/dotnet-dump) which allows us to extract either a Windows or Linux dump from our production environment. Usually most companies that I’ve ever seen fail at and doing production debugging at that very first step of, “how do I even match the dump with the version of the binaries and a version of the source code that was in production at the time of the crash?”

Now, luckily, in the .NET world, there’s this new technology called Source Link, which Microsoft does very brilliantly embrace nowadays. And most of all, I think all of Microsoft’s code is now using Source Link. And what source think does is it embeds a little JSON file into your PDBs. And I guess that sort of requires us to explain what PDBs are, because my experience is that most developers, like you know, that when you compile your code, you know, you get an EXE or a DLL but there’s always a PDB and until I actually started working on debuggers, I never really bothered to ask myself, “what’s that PDB actually for? Like, I know, it has something to do with debugging. But what is that?” Right? Have you ever wondered about that?

Jamie

I’ve never had the chance to really look into them. But I know that PDB - or rather, I think the PDB stands for like portable debugger or portable debug statements, and is how, when it’s running in live, and a crash happens, it’s able to look up sort of reverse lookup which line of code it was. And in the example of the old yellow screen of death, you get the actual line of code, not the IL, but the version of the source that it came from.

Omer

Absolutely, yeah. So PDBs are basically just mappings. Like they contain, well, one thing that contains the names of the actual local variables that don’t, aren’t sorted in the metadata. But the main thing that they give us is this mapping because let’s say you want to put a breakpoint, you know, Visual Studio highlights the line of code in red. That line of code, as we as humans we care about lines of code, but the computer doesn’t care about puny lines of code. It only cares about actual bytecode. So in order to set a breakpoint, we need to take that line of code convert it to the actual IL offset in the intermediate language code, and then at runtime that gets translated to the actual bytecode offset that the CPU sees. And we can actually set a breakpoint there.

Now, that’s great. But if you have a PDB, for your code that’s running in production, that’s not enough. You need to actually correlate that to the actual git commit. So that you can actually see the actual line of code. So Source Link is a technology that basically allows you to put in just one line of code or two into your csproj file. And what that build task does is it just inserts this very small JSON file into the PDB. And that JSON file just says, “Okay, so this PDB is correlated to commit such and such in this particular repository on GitHub, here’s the clone URL.” And if you have source link, installed and you’re using the latest Visual Studio tooling or the JetBrains Rider tooling, you can actually debug a dump file that was taken from production. And you will give you the exact version of source code that matches what happened.

Sponsor Message

I’d like to take a moment to tell you that this episode is sponsored by Datadog. Also stick around for the next 30 seconds to find out how you can get a free t-shirt!

Datadog are a monitoring and analytics platform which monitor your infrastructure, application performance, and log management.

Are you looking to move to the cloud, microservices, or .NET Core? Datadog can help with that. Their distributed tracing and APM provide end-to-end visibility into requests wherever they go. Whether it’s across hosts, containers, or service boundaries.

See for yourself! Start a 14-day trial today, and Datadog will send you a free t-shirt!

Find out more at datadoghq.com/dotnetcore - that’s datadoghq.com/dotnetcore - or check the show notes for a link.

Jamie

So that’s a pre existing technology that you can use. And if I can do that, and then clone the code and get the version of the code on my machine to threw the error, and I can see where the error is, how does production debugger differ from that then?

Omer

Sure. So the Oz-code production debugger doesn’t rely on you having those DevOps tools in place, we sort of give you all the various options. Because not all companies actually have the Source Link enabled or they don’t even, many companies don’t have a symbol server. So a symbol server is the thing that actually takes care of storing your PDB file so that you if you have a dump, you can actually find the PDBs that match that dump. Luckily, Azure DevOps can serve as a symbol server, but not many companies actually bother to use that. So the Oz-code approach is that we don’t rely on you having to have those things in place like a source server, Source Link, or a symbol server, we just decompile the code for you by default. So even if you never heard what a source symbol or Source Link is, we’ll still be able to give you a production debugging experience just using decompiled code. So you might not have the original source comments there and the formatting might be a little bit different, but you’ll still be able to figure out exactly what the issue is, and the only thing you needed to do is to just install the Oz-code agent. You don’t have to instal a NuGet package, you have to have any DevOps works in place. So that’s our baseline approach. And of course, we do also support the more fancy approaches to make sure that you can actually have your original source code if you set it up.

Jamie

Okay. See, I can echo the sentiment you said there about the symbol server. I think I’ve only ever worked on two projects that explicitly had a, “this is our symbol server over here.” And you know, the setting up of sending things in the right direction together all working. So I can totally agree that I think you could throw a towel into a room full of maybe 50 developers, and three or four of them will know what a PDB is, will know what symbol servers are, and know how to get from IL code through to original code via PDBs. You know, a lot of people have used disassemblers. Like, ILSpy and things like that. But to go from, “I have a binary on a server, through a PDB to the actual source code.” Very few people know how to do that. I didn’t know that Source Link was a thing, you see. So there’s another example. Right?

Omer

Yeah. I think that that situation might be now a little bit becoming better with Azure pipelines. So if you’re using Azure pipelines specifically. By default, if you use one of the original template, there will be a task there called index and publish symbols files, and symbol files are just as synonymous with PDBs. So as long as you don’t actually explicitly remove that task, Azure pipelines will automatically create source index PDB - so pdbs that have the correlation to the exact version of the source code in git - and it will store them so that if you’re using Visual Studio, you can just you know, add the, your Azure pipelines as a symbol server to Visual Studio - it’s just one line of settings - and then you can actually debug them. So you have from production.

I think, though, that, you know, this issue of how do we match the source code to the dump that we have in line is just one of the challenges like there’s there’s so many challenges to sort of keep people from doing production debugging. There’s this whole notion of compliance around dumps, which is another big issue with working with dumps, right,. Just saying the word memory dump, which we throw around very rapidly when we’re talking about production debugging. implicitly means that you’ve actually let a developer download onto their personal computer, the entire memory state of an application at a particular moment in time, including all the credit card numbers, email addresses, phone numbers, social security numbers, etc, etc, that are in there. And that’s a very, very problematic issue from compliance and regulatory constraints sort of standpoint.

Jamie

Oh, absolutely, absolutely. I know that the least in the EU, and in the UK, we now have a thing called GDPR. Which means that, as a developer working on a system, I shouldn’t see the live data, right, because that live data contains some form of personally identifiable information, regardless of whether it’s encrypted or not. It’s still there, right? So as a individual developer, regardless of whether my client or the company I’m working for or whatever, whether they want me to see that I don’t want to see that, right. So I don’t want to be working with what’s in memory on the real server. For that very specific reason.

And what if you take a memory dump? And it doesn’t just contain the memory of the application that’s running? Maybe that server has, maybe yeah, maybe went through the operating system of the server and said, “give me all the memory in a file,” right? Because I know that you can do that in Windows, I’m not sure about the Linux or Unix world, but you can say, “give me all of the memory, please.” Because then you can inspect the whole thing. What if your code is running there, but someone else’s code, maybe it’s a shared server, and it’s not being divided correctly read someone else’s code, which is doing something completely different because there’s a different company or something, maybe it’s a server that someone rents out to you or something, and they haven’t separated properly? Well, you’ve now got their working code in your memory dump as well. Right. So this is not just my code, it’s someone else’s, as well.

Omer

Yeah, I mean, it’s just a very scary thought in terms of, you know, not being able to debug, right because if you say you can’t, and this applies to logging as much as it applies to dump debugging, because personally identifiable information can very easily creep into log statements as well. And in either case you need if you don’t, if you’re not allowed to use dump files and you’re not allowed to use logging, then how are you ever supposed to actually fix an issue?

The approach that we took with the Oz-code production debugger is very unique I would say. In that, first off, we don’t work with memory dumps at all, you know, unlike other technologies, like the Microsoft technology. We only use the lightweight code instrumentation. And what we’ve done is we’ve treated redaction of personally identifiable information, anything that falls under GDPR and other compliance models as automatically redacted. And the way we do that is we sort of do a two pronged approach. So we both use, you know, regular expression, the pattern based approach to look for things like you know, what does a MasterCard look like? What is a visa Card look like? What does a phone number and email address look like? Etc, etc. And we also look at identifiers. So things like local variables, name method names, class names or assembly names and we look for things like the word “password” and “pwd” and every possible way you could misspell the word password and “CCV” and “SSN” and etc, etc. And so we sort of ship out of the box with these sort of sensible defaults for what information should be redacted. And then we make sure that that information never actually leaves the production environment. And because we’re not letting any developer download a memory dump onto their personal machine, but rather, we’re controlling the entire debugging experience through their web browser. That means that we can also supply a full audit trail of exactly what information was exposed to which developer and allow an administrator to have very fine grained control of what information needs to be redacted and also letting developers control that through code level attributes.

Jamie

That makes a lot of sense, I’m envisioning something like, “this is the production system. And we don’t necessarily want Jane the intern to know the details of exactly how it works.” Or maybe the details of someone’s address or some memory location, or maybe even you don’t want them to know, the URL of the production system, right?

Omer

Or the connection strings. Or the secrets.

Jamie

Yeah, right. You’ve said that production debugger gives you a, you have a URL and a facade to talk to, I presume, I don’t need to know as a developer of a feature that went on to the live system. I don’t need to know where production is, I don’t need to even see production, right? I just need to be able to see this debugger, right? Which then reduces the least amount of access required, right? I don’t need the production. I don’t need to see you at to be able to or test or release candidates or whatever you call your environment. But if I have these testing, and debugging systems, I can use those, right?

Omer

Absolutely. I think that our industry is slowly beginning to understand a very important, I wouldn’t say “best practice”, I would say must practice of nobody, not developers, not IT people, not DevOps people, not Site Reliability engineers, nobody should be able to get their finger into production, right? The only thing that could touch production should be the, you know, CI/CD pipeline that pushes code into production, and you have an audit trail of that, and you, you have access control on that. But no person should be able to actually access the production environment, no matter whether it’s in the cloud, or it’s an IIS server in your backyard or whatever it is. Because only bad things can come of that, both from a security standpoint and a reliability standpoint. And that is a big challenge of, “how do we enable production debugging and logging, but still, you know adhere to this very, very important rule that we, you know, we really ought to adhere to?” because otherwise, we’ll just get ourselves into a world of trouble.

Jamie

Absolutely. I guess that’s where tools like production debugger come in. Because I can debug live from a known error state. I’m not touching live, perhaps production debugger is or perhaps something that production debugger uses is touching live, like you say, you’re removing that access, you’re abstracting it away. I like the sound of that.

Omer

Absolutely. And the idea is that or trying to make the production debugging, not threatening by just giving you a web based experience that’s just like debugging in Visual Studio. Because from where I stand, I think that most developers find debugging issues that happen in production extremely threatening because they just don’t know what to do, right. If you give me a problem, and I’m able to reproduce it on my laptop, I know what to do. It might be extremely, extremely frustrating. It might take hours on end. But if I can reproduce it consistently on my laptop, I’ll be able to put a breakpoint and I’ll debug it. That’s what I know how to do. I’m a developer.

But if it’s happening in production, that’s just a very scary thought for most developers, like, how do I even work with memory dumps, and then the scary word [WinDbg](https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows-hardware/drivers/debugger/debugger-download-tools) is somehow thrown into the air, and then everybody just starts shaking uncomfortably in their shoes. And, it’s not a pleasant experience today. And I think that that creates a big disconnect. In this new modern world where DevOps and Site Reliability Engineers are becoming a big part of our companies, right. We have to be able to communicate with them. And I think there’s a big disconnect around the froing over the wall of a live site issue right. If something went wrong in production, usually, me Joe developer wouldn’t be the first person to hear about it right as a leader as a first year support engineer or a site reliability engineer. Those people have their own tools that they like to use, right. They like to use their APMs, their New Relics or Datadog, or Dynatrace, or AppDynamics, their application insights; and their Splunk for logging, or logsIO, or whatever it is, they’re using their Kibana, or Grafana.

And me, as a developer, I don’t necessarily care that much or one to know about those tools. I just want to use a debugger, because you know that’s the easiest way to really understand the root cause of a bug in my code. And this throwing over the wall of issues from the ops side to the dev side: currently we lose a lot of context, right? We, you know, we get a partial description of a problem. And we try to sort of conceptualise what happened or we just get an exception call stack. And the way I think about it, like an exception call stack is is just like you said, it’s a very, very problematic way of starting a debugging expedition. Because if we think about the code execution that led up to the bug as sort of like a crime movie where let’s say, you know, there’s just a terrible crime that went on. Then having the exception stacktrace is just like having only the last frame of the movie where you see, the bodies are all on the floor - or whatever metaphor you want to use - but you don’t know who was the murderer, what was the murder weapon, et cetera, et cetera. And then logging enables you to essentially put frame grabs, you know, somewhere in the middle of the movie here, here and here. And hopefully, if you do enough frame grabs, maybe you’ll be able to figure out the plot of the movie, but that might take a lot of frame grabs. This notion of time travel debugging that Oz-code is very much focused on is saying, “no, we should have a full fidelity time travel recording of every line of code that led up to the actual bug, because that’s the only way that developers can actually figure out a bug and once they figure out the bug, they can communicate much more efficiently with the DevOps people, the Site Reliability engineers and the QA personnel.”

Jamie

I really like that metaphor of like, it’s a heist movie, or, like you say, some sort of murder in your face like a police procedural story. Instead of having all of the little character defining moments with a police officer or the detective trying to figure this out, you just jump straight to, “there you go, I’ve stabbed him, and now I’m in jail.” That’s all you get who maybe the killer gets away. Maybe an exception is the killer has gotten away.

Omer

Yeah, it is often said that, “debugging is like being a detective at a crime scene where you just happen to also be the murder yourself.”

Jamie

Yep, exactly. I’m trying to shy away from describing the user interface of production debugger. So I don’t want to kind of describe the UI because I feel like it would be difficult to do in an audio format. But is there a demonstration video or something that folks can go to to get an idea of what it looks like, and what it feels like, and how it runs?

Omer

Oh, yeah, absolutely. So there’s lots of information on our website. So that’s oz-code.com. So folks are welcome to just go and have a look and try it out for themselves.

Jamie

Excellent.

Okay, so what I’d like to know is, have you any tips for let’s say, I’m not using production debugger, but I have a bug in my production code? What are the top three tips that you would give as someone who spent a lot of time working on debugging tooling, and because presumably, you’ve done a lot of pain driven development? You said earlier on that the debugging tools are not as good as they could be. And you’ve gone through this process of, .“how do I make this better?” And you know, you showed me earlier on some of Oz-code’s, debugging tools in Visual Studio, but what are your top three tips for debugging?

Omer

So there are several things: First, we already mentioned sourcing and making sure you have your PDBs. You know, take care, nurture, keep and provide for your PDB files.

One other thing I would say is that - and this is just the testing nerd in me - I would say that you should have a really good unit testing, and integration testing suite. So that as you’re trying to figure out the problem, and you get more and more hints about what is the root cause of the bug, if you can write an integration test or a unit test, or if you must, you know, just a throw away console app that you’re going to dispose of a minute later. But something that captures the minimum reproduction scenario of that bug, in isolated way that you can just run it and see that it fails. If you have that, that means that you have the bug trapped in a room that has no doors and windows, right? The bug has nowhere to escape.

Of course, you know, like all unit testing related advice, this is much, much easier said than done, right? There’s this whole science of how do we even make sure that we have, you know, a proper testing suite and can test at the right level of granularity? Like, do I need a unit test or an integration test or a UI test to to reproduce this particular bug? But if we have that, that will not only make us much more effective at actually solving the problem, but also has the nicety of hopefully getting into our CI/CD pipeline as a regression testing, making sure that problem never creeps back into our production system. Does that make sense?

Jamie

Yeah, that makes perfect sense. If I’m able to create a test, which recreates it, I like to keep the test around, and just leave that as part of the suite of tests. Because then you’re protecting against regression. You know, that when the code gets back up to production, it’s gone through at least one pass of automated testing along the way. And as long as you were able to, like you say, capture that bug, as was described, I won’t say, “capture the bug fully” because, like you said, there’s parts of the description that aren’t there. But let’s say it’s some kind of validation on a field, and you’re supposed to be able to input between zero and 100. But when the user enters 50, everything goes wrong, right? You may know that when they enter 50, everything goes wrong, but you may not know that when they enter 25 it also goes wrong. And that’s why I try to step away from code coverage and more a case of when I’m looking at unit tests. If this block of code can accept a range of answers, have I covered all of those possible inputs? Like I said, if your code can handle numbers between zero and 100, there are 101 states, zero all the way to 100 that are valid, and billions of possibilities that you know are invalid. But do you know that all of your valid states going in work? And I think you could use test theories if you’re using xunit, but I don’t think there are that many ways in .NET to inject, “here are millions of different combinations of the inputs.” But if you can do that that helps, I think.

Omer

Yeah, absolutely.

Sometimes you have to hack the system in order to be able to test efficiently, right? Like one example that I could think of from what we’re doing in the production debugger is that: the production debugger, the way it works internally is it’s using bytecode instrumentation. So it’s actually taking the IL code that’s running in your production system and injecting its own hooks into that dynamically using a technique called RE-JITting. So we can turn that instrumentation on and off on the fly. And that’s how we also preserved performance. But doing bytecode manipulation of .NET code is extremely, extremely difficult and intellectually challenging and error prone. And it’s the worst kind of error prone: it’s error prone in the sense that you made a mistake, you’re actually crashing somebody’s production environment. And to sort of try and mitigate that risk. What we’ve done is we created an automated exploratory testing, we said, “look, there’s so many combinations here,” like you alluded to earlier, just the vast amount of combinations, “there’s no way our testing engineers can look at all those difficult combinations, because there’s just so many of them.” So what we ended up doing is we created what we like to call our crash monkey, which is a an end to end test that goes in just downloads, the monkey sort of downloads open source projects off of GitHub. So we look at, you know, json.net and protobuf and many many other different projects covering all the various types of .NET that you can run nowadays. And we run their unit tests under a special mode where we instrument every single method that is running. And that allows us to sort of turn the problem on its head to try and do automated exploratory testing: like figure out heuristics where we can have a test that for itself tries and expand its own test space.

So we do a lot of funky things like that to try and you know, make sure that we are covered, but it is a very, very difficult and problematic question like, “how do we have, how do we even manufacture a test suite that is worth its weight?” like, right, because it’s it’s a heavy burden to have a testing suite. It’s something that you have to maintain, tests fail, tests take a long time to run, you have to work on making sure that they’re fast, reliable, you know, atomic and all that good stuff. And that’s a big effort and if you’re not getting your efforts worth then why have tests in the first place? Right?

Jamie

Yeah, yeah. Who tests the tests?

Omer

Absolutely. That’s a brilliant point. Yeah. I could speak for hours just on this topic of testing. Because I think that as an industry, we’re maturing into it. We kind of talked a whole lot about unit testing in the early 2000s. And then we kind of let go of it. And then we sort of are in sort of like a steady state of half way doing testing halfway, not doing testing. But I think that that just the practices and the tools will both mature over time. That’s the best we can hope for.

Jamie

Sure. Yeah. I mean, you just have to remember that our industry is incredibly young, you know. Not just .NET, but the whole, “using an electric computer, a mechanical device, an electromechanical device that will calculate something for you.” You know, we’re talking 1930-1940. So we’ve only been around for 90 or 80 years, 80 or 90 years depending on how you measure it. So yeah, writing software for all of these devices, is still an incredibly young industry. So yeah, unfortunately, we are going to get a few things wrong. And unfortunately, we are going to have to grow because of it. And I think that the debugging tools, like you’ve said, are a great way of getting started figuring out how to, actually, “how do I do this? How can I build a tool to do this? How can I use the tools that are there?” And like you say, I think that the whole industry is going to mature because of this drive towards quality. I think that hopefully - I would hope in the next few years, a lot of the big developers and people who do like the state of DevOps reports will likely come out and say, “right, stop just pushing to production a million times a day, because you want Netflix and you can’t afford to do that.”

Omer

Yeah. How about we move fast and maybe not break as many things right?

Jamie

Yeah, right. Yeah. Move a little bit slower, break fewer things.

Omer

Absolutely. Yeah.

Jamie

Do you have a number of resources for learning debugging in .NET, right? Like you said, we all know, “hey just put a breakpoint in and there’s a stack trace and you hit F10.” Right? You just keep keep hitting F10 till the exception happens, and then you can see it and then you move the breakpoint and you carry on. Right?

One of my earliest ways of debugging was divide and conquer. I have 50 lines in this method, I know appears somewhere. I’ll put a breakpoint at line 25. And if it happens before, then I’ll go to line 12. If it happens before then I’ll go to line six. That’s good. But it takes a long time to get there. Right. So yeah, what are some of your resources for learning, effective debugging?

Omer

This is going to be a bit of a promotional plug, but not for myself for a dear colleague of mine. So my colleague Michael Shpilt, just wrote a book that’s called “Practical Debugging in .NET” And it’s a fabulous book. The website is practicaldebugging.net. I’ve been trying to do my best to find a few hours here in a few hours staring on my weekends to try and help edit the book. And it’s a from reading almost all of it by now, I think it’s a very, very fabulous look into, “how do we debug all the various problems that we have? So memory issues, memory leaks, GC pressure, how do we work with dump files? How do we become more effective in debugging code inside of Visual Studio?” So absolutely recommend that. That would be my number one recommendation right now.

Jamie

Sure. There were a lot of words are used there that I think maybe, especially Junior .NET devs, may not know about, like, they may know about the grabage collector, right? The GC, but they don’t know about GC pressure, right? Or they may not know about some of those techniques. So I may have to leave it an exercise to the listener to go and look some of these things up. But there is, is a helpful glossary on I think the Microsoft documentation of what the garbage collector is and a 10,000 foot view of how that all works. Right?

Omer

Right. And I think that nobody really explains these things really well and they’re hugely important. Because when you’re talking about debugging and troubleshooting memory in .NET, is a really big issue, right? We think, “oh, there’s no, it’s a managed runtime, right? It takes care of the memory for us.” But actually, some of the biggest issues that you see in production systems in .NET, revolve around memory. And just knowing, you know, “how do I use a memory profiler? How do I use a memory profiler to solve a memory leak?” versus, “how do I use a memory profiler to solve GC pressure?” which is a completely different technique. Those are things that nobody really teaches you and are hugely important if you are to be able to become you know, a senior developer that can handle whatever a live site incident is thrown their way, right?

Jamie

Absolutely. Absolutely. I think maybe part of that is because if you look at like the history of .NET, you know, it was originally meant to be a language for creating enterprise apps that live on an intranet, not a thing that serves websites and web applications and micro services - more buzzword bingo - that happen all over the world. And not this technology is supposed to be able to run on refrigerators or on your watch, or, you know, it’s evolved so rapidly that I feel like maybe the tooling is having to play catch up. And the education around the tooling is having to play catch up. And I feel like we can’t really blame anyone for that. And it’s certainly not Microsoft’s fault, I don’t think because it’s not their fault that we’re playing catch up, because maybe we should be the ones looking into it rather than being told, “hey, go look at this thing. And hey, go learn that.”

Omer

Yeah, absolutely. The Microsoft sort of bubble has its issue, I thinkm it’s fair to say with people looking for the Microsoft solution, or the Microsoft library for every problem that they face. I think that that’s one place where the .NET world maybe needs to grow and mature a little bit compared to, you know, the Python world or the Java world where the developer community is a bit more self sufficient, I would say in that regard.

But yeah, good tooling is something that’s coming in from all different places, and sometimes good tooling means you as developer figuring out, “okay, I should write a tool for this particular problem that I’m having today. It might take me a while. But if it’s more efficient to do that than just doing it manually, then, you know, it’s my job as a developer to write code that fixes the problem.”

Jamie

Absolutely. I was actually explaining to my brother earlier on today, he said, “you developers, you just sit there and look at text all day?” And I said, “no, no, that’s not it at all. Developers don’t write code. Because 90% of your time is not writing code is fixing the bugs, right?” Which hopefully, things like production debugger will help with, but I think of myself as someone who creates solutions. Because something that say a client comes to me or someone comes to me and says, “can you write me a program that does this?” And I go, “I could. Or you could use a spreadsheet.” You know, that’s instantly problem solved.

Omer

Right.

Jamie

Because that’s what we do. Because I mean, I don’t know about your work, but 90% of my work in the past has been “have ever tried using a spreadsheet?”

So what about keeping up with yourself and Ozcode then? Is there - obviously there’s oz-code.com, and presumably there’s a Twitter and stuff - but if folks after hearing this want to learn a little bit more about testing, or debugging or production debugger, is it “go chase after Omer” or is it go to Ozcode? What’s the process?

Omer

So I’m at @OmerRaviv. And if you do a Google Video search on my name, you’ll see various talks that I’ve made Channel Nine on Microsoft on things like, you know, performance and reliability of Visual Studio extensions. But those talks actually talk as well on like performance testability and, and memory management in .NET. That apply just as much to any .NET application as much as they apply to writing a Visual Studio extension.

Jamie

And you said that there was a demo website that folks can use? And is that hanging off of the Ozcode website?

Omer

Yes. Just go on the Ozcode website and play around.

Jamie

Excellent. I’ll put links to all of those things in the show. And I think, because I said earlier on, I don’t like the idea of trying to describe something that is visual in an audio context, because it’s so difficult to do. And then if you and your team decided to change the way the UI looks a year’s time, what I’ve said is mostly useless, right?

Omer

Absolutely. Yeah.

Jamie

Definitely check those out. I’ll put links to those in the show notes. I’ll put a link to the book that you’d mentioned as well, because that sounds interesting. And I may have to reach out to your friend see if they’d like to be on the show as well.

Omer

Awesome.

Jamie

Yeah, there would be quite cool. because like you said earlier on, there’s there’s this whole debugging area that almost no one talks about, you know. I remember, when I was at university, we did C#/.NET - so this was 2002, this was like .NET version 1.1 or something like that, right - and they’re like, “brilliant here’s Visual Studio. Here’s all of the tools. Go do it.” And I was like, “I’ve got a bug.” And the lecture went, “okay, debug it, then,” And I was like, “how does it work in Visual Studio? Right? I’m used to doing things…” because like before, then I done low level C on PIC devices. So I know that tool. I have no idea with this. Okay, well you could do is there’s again a stack trace and all this kind of stuff. And then he walked away. And I’m like, that doesn’t actually help me to actually debug the problem.

Omer

No, it’s the one thing that you don’t get taught at university or even in college or professional trade. They teach you Computer Science without teaching you debugging even though debugging is literally what you do , for research says 50% of your time. So that is always sort of perplexed me how that is that they just don’t teach you how to debug and that that is a big part of the problem right there.

Jamie

Absolutely. Yeah.

So what I’ll do is I’ll put all those links in the show notes and people can go check those out. And yeah, hopefully I can figure out a way of doing a series of these episodes on debugging because it is a topic that like you say it’s important for us developers to know about. And especially in the .NET world, I feel like it’s not really that well talked about. It’s just sort of assumed, “yeah, you’ll go and debug your code. And you’ll know how it works.” And like you said, earlier on, you mentioned minidump and winDbg, and, you know, these tools that would scare people off because you’re looking at just a table of hex characters. Right?

Omer

Right.

Jamie

Hopefully, I can be a tiny cog in the change of that, to get more people thinking about debugging in a more proactive way.

Omer

That’s awesome.

Jamie

It is awesome. Let’s see if we can do it. Let’s see if we can do. But yeah. Thank you Omer very much for spending some time with me today. Like I say, I know, it’s really late for you, not only for me, but really for you because of the time difference. So thank you ever so much for that. And yeah, it’s been a real pleasure talking to you about debugging and the production debugger.

Omer

Thank you very much, Jamie. It was a real pleasure to be here. I really enjoyed it. Thanks a lot.

Jamie

Thank you.

The above is a machine transcription, as such there may be subtle errors. If you would like to help to fix this transcription, please see this GitHub repository

Wrapping Up

That was my interview with Omer Raviv about the difficulties involved with debugging in production. Be sure to check out the show notes for a bunch of links to some of the stuff that we covered, and full transcription of the interview. The show notes, as always, can be found at dotnetcore.show, and there will be a link directly to them in your podcatcher.

And don’t forget to spread the word, leave a rating or review on your podcatcher of choice - head over to dotnetcore.show/subscribe for ways to do that - and to come back next time for more .NET Core goodness.

I will see you again real soon. See you later folks.