Episode 55 - Integrating With External APIs With Alexey Golub

Embedded Player

The .NET Core Podcast

Episode 55 - Integrating With External APIs With Alexey Golub

Supporting The Show

If this episode was interesting or useful to you, please consider supporting the show with one of the above options.

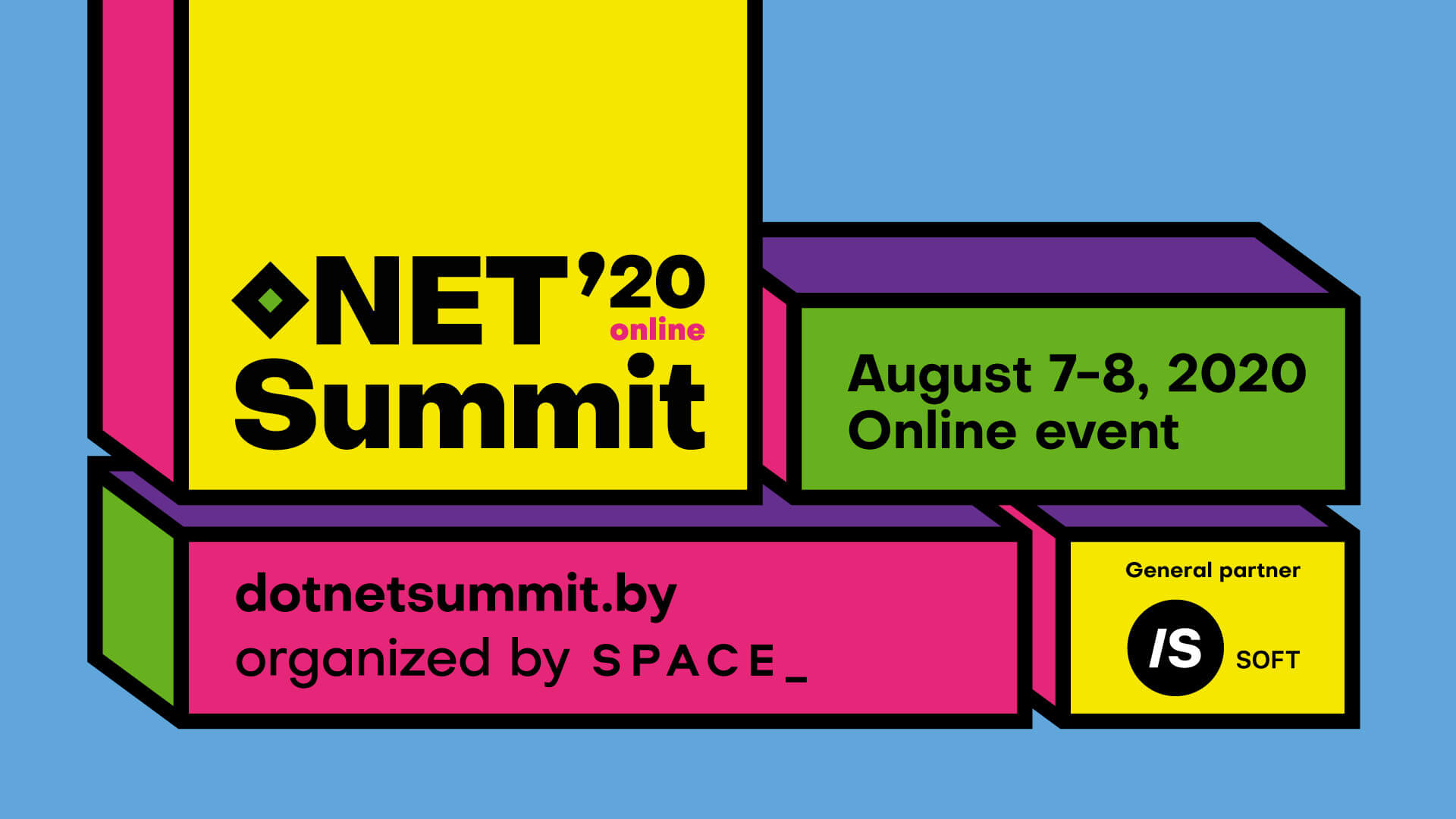

.NET Summit 2020

Have you heard about .NET Summit? .NET Summit 2020 will be held online on August 7 and 8 (3pm-7pm GMT+3). Speakers include podcast alumni Dylan Beattie, and this episopde’s guest Alexey Golub. Check the website for .NET Summit for updates.

Regular tickets are on sale at 65 EUR - get yours before price increases on July 28 - at

https://dotnetsummit.by/#tickets. Listeners of the podcast can get a 15% discount by using the discount code DOTNETCORESHOW15 at checkout.

.NET Summit 2020

Episode Transcription

Hello everyone and welcome to THE .NET Core podcast - the only podcast which is devoted to:

- .NET Core

- ASP.NET Core

- EF Core

- SignalR

and not forgetting The .NET Core community, itself.

I am your host, Jamie “GaProgMan” Taylor, and this is Episode 55: Integrating With External Apis With Alexey Golub. In this episode I talked with Alexey about two of his open source projects - CLIWrap and YouTube Explode - and some of his top tips for integrating with un-documented and unstable APIs.

So let’s sit back, open up a terminal, type in dotnet new podcast and let the show begin.

The following is a machine transcription, as such there may be subtle errors. If you would like to help to fix this transcription, please see this GitHub repository

Jamie

So the first thing I want to say Alexey, I’m assuming it’s Alexey I’m not sure on the pronunciation.

Alexey

Yeah, yeah, that’s correct.

Jamie

Excellent. Excellent. I’m not usually that great, pronouncing people’s names if I’m completely honest. But the first thing I want to say Alexey is, thank you ever so much for spending some time with me this afternoon because, well, I think you’re an hour ahead of me. So it’s a little bit later into the evening for you. So, you know, I totally appreciate that everyone’s really busy these days, even with, you know, I mean, it’ll date when we’re recording this. But you know, most people are working from home, but even so, it’s still quite late in the evening. So thank you ever so much.

Alexey

Thank you for inviting, it’s actually my pleasure. So yeah, that’s great.

Jamie

Okay, so for the people who are listening, would you mind giving us like a brief introduction to like, the work that you do and the kind of projects that you work on and stuff?

Alexey

Sure, right. So I work mostly in .NET. So I’m a .NET developer, during my work time, or like daytime work, I usually work on the cloud, micro services, like using Azure, AWS, ASP .NET Core. Basically all the trendy stuff.

When I come home, I usually work an open source. So I like to spend quite a lot of time on open source, I sometimes contribute, but mostly maintained my own projects. Yeah. So basically, I suppose most of my experience in development comes for my open source projects. And that’s probably it’s really, also sometimes, you know, talk at different conferences, but I wouldn’t say that’s, that takes too much of my time. So I probably shouldn’t even mention that too much.

Jamie

No, that’s fine. I find it really interesting that closed source is something that a lot of people say that Microsoft and Apple invented it. And then open source is kind of how our industry started. And when people come to me and say, “How do I get started? How do I get loads of experience?” and I’m like, go make something find a problem in your life or maybe not a problem in your life, but a problem that you have with a computer or some kind of hobby that you like to do, and see if you can make something that is connected to, because then you’re taking that that problem that you have, and breaking it down into all of these little requirements. And if you wanted to go down the route of making user stories, and all that kind of stuff, all you just make it, right, you have this problem, you want to solve it, you then go and solve it and give it to the world for free. People will then likely find it and go, “hey, I’ve had this great idea. I’ve had this problem. Let me make a little tweak to it.” And then you’ll learn even more, right?

It goes back to that idea of go read source code.

Alexey

Right, right.

Jamie

A lot of the older folks and you know, I have a beard, and I’m quite old myself, but the “old guard” will say go read source code, and you get better at it. And it’s like you can or you can go and build something.

Alexey

That’s true. Like when I when I started, I didn’t actually have a goal to you know, start doing open source. So it wasn’t like, “Oh, I want to do open source. What should I do to start right?” So it was quite the opposite. I had, like you said a problem that I could solve with programming and I decided to do it. And once I did it I thought, “maybe it could be useful to somebody else. And so why not open source that right?” I wasn’t really intent on making money out of it. So why not just open source it? That’s how it started? Pretty much.

Jamie

Sure, sure. And I mean, we’ll come on to it later. But there was something that I built today. For my brother. He’s had a problem we were discussing off air. One of the things he does is he does video game streams. And one of the ways that he does that is he streams up to twitch, but also records locally at the same time. And the problem is, he’s got a two hour long stream that’s seven or eight gigabytes in size, and he wants to upload it to YouTube, but YouTube saying “No, that’s too big. So, you know, I wrote a little app that will, he just wraps around FFmpeg. And it throws all of those files at you run it in a directory, it will just re encode every single file in that directory for him. And that’s useful for him. It might be that because he’s not a developer or - he is very much an IT person but he’s not, you know, the level that you are, I would be at. And so some of his friends who are also streamers may find this useful.

Alexey

True.

Jamie

And you talked a little bit about how sometimes you’re involved in conferences as well. And I think that can be a great help to anyone in the development space, right? Like, even if you don’t get up and speak. I was at NDC in London this year, and just walking around and saying hello to people and introducing yourself.

Alexey

Yeah.

Jamie

You meet so many people, you got all of these contacts. And somebody somewhere will say, “hey, do you remember we talked about that we were standing in line to get lunch. And you said, there’s this package that can do this one thing? Well, guess what, I need to know what that package.” Right? I think you can save time or they say to you, “hey, I’ve had this great idea. And I think you’re probably the best person to talk to about, let’s make it,” and then you go and make it right. And then you make millions of dollars, right?

Alexey

It’s actually it’s true. Like when I was just you know, working as a developer and starting out, I sort of viewed what I was doing and what what other people were doing completely separate. Like I thought they were in different bubbles sort of thing. And it’s only when I started Going into conferences as, you know, just as a participant that I started seeing those people face to face that they’re, you know, physical, I can talk to that I can ask them questions that I started to realise that it’s just a big community and we’re all part of it. And it’s actually a really nice and motivating feeling, I would say.

Jamie

Oh, definitely, definitely. And then I like to pick talks that are some of them, I pick because they are what I’m interested in. And some of them because they are literally nothing to do with what I usually do, or any technology they usually touch So at NDC, I went to a talk about Apache Kafka, no idea about Apache Kafka. And watch the person who gave the talk - Alan Underwood - talk about how great it was to run this thing with loads of Java and all these Docker things. And I’m like, “I totally I no idea what you’re doing. But I totally get how this is really useful.” And then I went away and looked into Apache Kafka and all just sort of fell into place. This is what it is. This is why it works and all that kind of stuff. And whilst it’s out there, of the .NET space, he’s given me an idea of similar things within .NET that I could use to solve similar problems rather than writing it all myself.

Alexey

Yeah, that’s actually very important. And I think it’s, that’s one of the main reasons I always tell people to, you know, learn another language for maybe multiple languages. Because even if you’re not going to, like use it, you know, at your work or whatever, you’re going to learn how to approach the same problems from a different angle. And that actually makes you understand, like, the original angles from which you were approaching the problem is a lot better as well.

Jamie

Absolutely. One of the things I always say to the juniors is, “okay, so you’re learning C#, recall, learn Java, because it’s semantically similar. Now that you understand C# and Java, grab a look at C++. And you can see where the ideas have come from.”

Alexey

Yeah.

Jamie

I think Scott Hanselman has this idea of learning three languages: a object oriented language, a functional language, and a scripting language. And then you can understand how you got from one to the other.

Alexey

Right.

Jamie

Because once you’ve learned those, then yeah, you can see how the ideas for where the C# come from, well, a lot of people don’t like to say this, but C# came from Java. Java came from C, and you can see this big lineage of these languages coming together. And then yeah, you get a better appreciation for the decisions that were made in putting these languages together and you, you then start to see how like, C# is very slowly nudging everyone into this Runctional direction, right?

Alexey

That’s also another thing is that when you’re, let’s say, writing in C# all your life, you might think, “Oh, this C# feature isn’t that great. I wish I was liking Go or something.” But then if you actually tried to write that in Go, you’ll realise that it’s, in fact, just a trade off and you’re going to you know, have other maybe disadvantages that you weren’t aware of before. And you know, when you actually try that and look back and you start to realise that, you know, the design is actually really good and there are trade offs that were, you know, taking for good reason, and it just changes the way your perspective, really of the language, and the platform, technologies, everything.

Jamie

Absolutely I agree, I really do know like duck typing. But I appreciate the things that allows you to do. You know, like they really quick prototyping and wonderful things like Angular and React have been built on this idea. So

Alexey

Yeah

Jamie

As much as I dislike it, because I’d really like to be able to go dot and see all of the properties or to be able to set a variable to a specific value and know that it’s going to be that value and have that compile. It’s call me an idiot, if I tried to do it wrong, you know?

Alexey

Yeah, for sure. I think a lot of people would have been happier if JavaScript was statically typed from the beginning.

Jamie

But then you look at the history of JavaScript, and it kind of makes sense as to why it’s not. Again, it’s that trade offs thing you were talking about earlier on you.

Alexey

Yeah.

Jamie

There’s that famous story of JavaScript was first created in 10 days. Makes perfect sense to me. You’ve got 10 days to do it. Okay. Let’s not bother with the typing system. Yeah, yeah.

Alexey

Yeah, we’ll implemented later. Just you know, it we need it, we’ll do it.

Jamie

One of the things that I really wanted to talk to you about is your library CLIWrap. I used it this afternoon in an application I kind of hinted earlier on. And the application I threw together was maybe 14 lines of code. And it is, “grab me all of the mp4 files in this directory, and throw them all FFmpeg, and output to the screen what it’s doing.” It’s brilliant.

Alexey

Yeah.

Jamie

Whereas previously, I’d have to like System.Process.NewProcessInfo and all that kind of stuff.

Alexey

That’s actually almost the same reason I created in the first place. So I was doing something with FFmpeg as well. I was muxing streams together. So I had two streams, audio and video. I wanted it to be combined. And also like you said, I started this System.Diagnostics.Process, the built-in .NET class and tried to like use it to run it. And well I googled like, “how do I for example, read STDOUT or STDERR?”, “How to wait for it to complete?” Like the first issue was that it’s, it’s synchronous, right? So <code>WaitForExit</code> it doesn’t return a Task; and a process being you know, naturally an asynchronous operation, you would want that to be expressed as a Task. So it didn’t do that.

On top of that, like when you try to read STDOUT/STDERR, If you do it incorrectly, which is really simple or easy to do, you will get a deadlock. Like it’s very simple to get into a deadlock scenario. So basically, I spent way too much time trying to get it to work and I realised, “okay, it has to be simpler. And if it’s not already simpler, I just have to make it simpler.” So that’s how the project really started.

Jamie

Just to give a little bit more background information. My understanding CLIWrap, having used it today is that it kind of wraps around calling command line stuff. So you know, we both talked about the example they were using FFmpeg, but maybe we want to use something else, like disk utilities or something like that.

Alexey

Git.

Jamie

Yeah, exactly right, we want to pull some code from git in a programmatic way. Right? I know that the goal was to sort of simplify that original task that you have. But was that literally the only thing you were trying to do?

Alexey

It always started with a single task, right? And then it starts to evolve. Yeah, basically, I just wanted to make my life simpler for that particular scenario. But I realised that it’s very generic, right? So I just want to launch a process. And I want to treat it like a CLI, so I don’t expect it to have like a window with buttons. So just, it’s just kind of gonna be a common line application. And I just wanted to like run until completion. And I want to know what it brought to like STDOUT and STDERR. Basically, that was it at the beginning.

And just like you said, a lot of scenarios fall into that description. For example, you can use git or kubctl or some other CLI that you want to automate. And it also makes sense because, you know, when you want to use some code like FFmpeg, why are we using FFmpeg as a CLI? Because there is no library in .NET for doing that sort of thing. So instead of, you know, trying to write a library for that, which could take years, probably, you could just take FFmpeg and wrap it and pretend like it’s managed from the beginning, right, so you can just hide it behind the layer abstraction. And I thought that was really cool. So you could just literally take a binary and pretend it’s part of, you know, a library or something like that,

Jamie

Like you say, you know, you could spend years building a .NET wrapper around something like FFmpeg. And then as soon as the API space changes, you have to go back and rewrite everything. Or you’re then locked to distributing that particular binary, that version of that binary with your application, which then potentially has licencing issues. So yeah, I totally get it. The only dependency then is that the consumer has whatever library and knows the API, presumably they would know it anyway, because all they’re doing is automating.

Alexey

Right. Yeah.

Jamie

And you know, I’m sitting here thinking, well, I could totally do that with something like, I use Hugo a lot for some of my static sites. And maybe I could use it with Hugo right?

Alexey

Right. Yeah

Jamie

Just run a little cron job once a day to just rebuild my site.

Alexey

Yeah, eventually.

Jamie

So we talked about, like, how it came to be. Have you only used it with FFmpeg or have used it with not that FFmpeg isn’t complex, but a much more complex situation.

Alexey

Actually, even as with FFmpeg, is then a pretty complex situations like for one of the cases was when I had an HTTP stream that I obtained through HttpClient. I wanted to just pipe it directly into FFmpeg without having to save it to a file first so that it’s you know, faster, and you don’t have to waste space on the hard drive and whatnot. And you know, I could actually do that with CLIWrap, because you can pipe streams and you can pipe commands into commands and you can do all kinds of crazy things. And that was actually probably the most difficult thing to design and implement. And it wasn’t until version three of the library that actually I think I got to it right. Because I’m not sure for you know, maybe it turns out it doesn’t work for some scenarios, but so far, it’s been really nice.

Oh, and another thing I wanted to mention is that I’ll use it a lot for testing, actually. So I have like one other library, which is an auto updating libraries. So it basically does what ClickOnce or Squirrel does, but it’s much less opinionated. So you basically take a dependency, you say that, “okay, take this GitHub repository, look for latest release, and if there’s something newer just replace it,” and to test that I had to make another application that would sort of be the dummy application that would get updated. And to automate all that I just used CLIWrap. So it actually saves myself a lot of time just doing that.

Jamie

I’ve made open source packages in the past and then found, “oh wait. I can use this to…” and you know, in the end, this map of “oh cool, I have this, no longer have a hammer and I have a screwdriver I can screw the screws in. And then the screwdriver will help me build a lathe or something. And you end up building these bigger tools.”

Alexey

Yeah.

Jamie

And the way that I did that was when I first got into ASP. NET Core back in the day was I thought, “well, I want to create the OWASP Recommended Security Headers.” And I thought, “well, how am I going to do that? Well, let’s have a look at how headers are injected. Oh, it’s middleware. Right? Okay, so let’s build a middleware.” And so I taught myself how to build middleware. Now we’ve got like, four or five different ASP. NET Core middleware is just laying around the place. And almost every project I start that is either a web API or some kind of web UI has all of those middlewares installed. Just because I’m like, “hey, like you can see it and use it here,” but also helps with the keeping those NuGet package install numbers high.

Alexey

That’s true. That’s, that’s, let’s face it. That’s the main reason.

Jamie

Yeah, right. That’s it. Yeah.

We mentioned earlier on about the troubles that we would have for creating an API that talks to some service or some application. And that constantly changing or rather constantly evolving. We said that, “with FFmpeg, if you were a .NET wrapper around it, and then they change the API, you’d have to go back and revisit,” right?

Alexey

Yeah.

Jamie

And I happen to know that you’ve been working on an application called YouTubeExplode.

Alexey

it actually has a funny history for that name. I wanted to make an experiment, right. So I just wanted to download a video off of YouTube. And I thought, “how hard can it be really.?” And my experiment started from googling, obviously, and the first like, few examples that I’ve seen were all in PHP and PHP, there’s this function that takes a string and splits it and it’s called explode. And I saw that function everywhere because, you know, you have a lot of URL encoded data and you split by semicolons, or commas I think, and then you use that function all the time. So I thought, “oh, that’s a good idea for the name. So what called the library that instead.”

Jamie

So is literally just a YouTube downloader or does it do lots of other things? What’s it do?

Alexey

It’s actually hard to explain what it is in one word. But it does a lot of things that you would normally be able to do when you, you know, open YouTube in a browser, but you wouldn’t be able to do through the means of the API, because those are not provided. So if you were to download like a video, or you wanted to get like the videos in a playlist, or closed captions for video, all those sort of things, you could do that with the library. Yeah.

Jamie

Okay. So it’s that kind of multi tool for YouTube, then.

Alexey

Yeah, essentially.

Jamie

That’s interesting. So the reason I brought that up is because we were talking earlier on about, “API’s are constantly changing, right? And if an API is closed, then is always going to change, right? Because it’s up to the person who are the people who are maintaining that API.” So my question to you is

Alexey

how do I do it?

Jamie

Yeah, right. And why? Right, because I can just imagine, you get something working you push out a build, and it works. And then 30 seconds later, everything’s broken.

Alexey

That happens.

I could answer why is because I didn’t really think about it like that when I started it sort of just was an experiment. I didn’t think I would have to maintain it for what is it four years now, I think. But like as it kept going, I also have this problems, but sometimes they will just break. And I would have to fix that. And then people would create issues saying, “when it will be fixed? Why is it not working?” And then I started thinking, “what can I, like how can I approach this problem in a way that I can avoid making fixes as much as possible?” like so that it works most of the time, whereas as long as possible for breaks again.

And there are basically like some things that I’ve found that are, I would say, good approaches to that. So let’s say you were building let’s say just a normal client to an API that has, you know, a solid versioning system and you’re sure it’s not going to change. What would you do? You’re probably just make an HttpClient, you would use System.Text.Json or NewtonSoft JSON Deserialise to your like models and stuff like that. And that would work perfectly.

And obviously, when the API is changing all the time, or when it’s not supposed to be consumed from the outside, that won’t work, right? Because as soon as something changes, your deserialisation breaks. And I found that it’s actually a big problem when you rely on specifics. Like when you bind the, the model of your domain entity, essentially, let’s say video right: that has some fields may be a title, author and stuff like that. When you sort of bind that logically, with the response you get from the API, you’re gonna have problems if that API changes a lot. And you get that with the deserialisation because it maps them one to one, right? So of course there are like converters and stuff like that. But essentially, it’s still one to one mapping.

And the first thing I realised that I could actually, if I could sort of break them away or break them apart, so they’re not coupled as much, then I probably would be able to save myself a lot of headache. So, because of that I’m not using deserialization at all. So I’m dealing with JSON, but I’m always doing all the parsing manually. So I have like this model that I’m telling the my consumers that I’m going to return. But in reality, I might actually make multiple requests, or I might take like this field from one place, or this field from another place. And it’s actually hidden behind the layer abstraction. And that gives me this flexibility that, you know, if that changes, I don’t actually have to, you know, make a breaking change in my library. And also, because of that I can implement like multiple layers of fallbacks. So if I, let’s say, I need an author of a video, right? But if I make this request and might be there, but let’s say two out of 10 cases, it’s not there because there are multiple types of videos and they have like different constraints or whatever. So I would instead go into another request or send another request and get it from there, but it’s going to have a different name. And it would be impossible to do that if you’re just deserializing stuff.

Jamie

I like that approach, because we’re always all of us in our day to day lives, unless we’re doing something wonderful like making video games or whatever, almost all of the time: our code talks to an API, which more than likely talks to a, another API, which then eventually will maybe talk to a database, and it will talk back to us, right. So I like this idea of, “what if the API that I’m consuming breaks?” In like The Pragmatic Programmer, they talk about Design by contract, but what happens when that contract breaks?

I like the idea that you’ve come up with like, “I will have my model, I will take the raw output, I’ll get the bits that I need. And then if I need something else, I’ll go back and get something else.” It’s kind of like a there is a pattern that I’ve been using a lot recently for Entity Framework where I have a generic repository. So rather than, “give me the entity and all of the related entities,” I’ll get the entity and all of the IDs, fro the related things. Because nine times out of 10… I’ve actually seen this in the wild where someone will create a model for logging in, right, you put in username and password, and it will go to the database will get the user data. But there’s also the navigation properties for like, orders and addresses and payment details and all of that comes back. And it’s just to check whether they can log in or not.

Alexey

This is actually an important point as well that you’re brought up, and that is: when you design this contract, that you’re essentially guaranteeing your consumers that you will return, you have to really be confident that you’re always going to be able to return all of it right. And when I started I didn’t realise that well enough. So I obviously I wanted to do that but I didn’t know what exactly what kind of like fields would go together, and which ones wouldn’t. Because when I started I looked at the internal requests that YouTube’s front end uses, and I saw that, for example, this request returns all this kind of data. So I just put it in one contract that I promised everybody I would return,. But then they suddenly removed some of the fields or move them to some other place, and I have to make another request to get it. But then I realised that those fields weren’t really that important for like another heavy potentially request. And it would have made sense to like, separate them from the beginning.

And from that perspective, like, for example, take a playlist, right? It has videos, and but playlists also has its own metadata. So it has like title, again, author date, when it’s created and stuff like that. And logically, you would think that, okay, I want to get the playlist, I will get the metadata associated with it, but I also got the videos, right. But that’s probably not a really good idea. Because again, those are two essentially unrelated things like unrelated even concepts, I would say. And it actually It saved me a lot of times that I separated them, because then I could think of them separately. And if I needed to, like optimise one of the requests, I don’t have to worry that I might not have enough data for the other, you know, sort of model that I’m trying to return. So another thing I guess taken away from it is that you should really think hard and limit like the scope of your models as much as possible. Even if it’s very fragmented at the end, like you will have very little data in one model and you have to make many requests, it will actually save you headaches. Also because like even if one of them breaks, the other one might not break: your Playlist.GetVideos might break, but Playlist.GetMetadata might still be working. And let’s say half of your users are only using the metadata parts for some reason. And then you’ll have half as many issues on GitHub. So it really makes sense.

Jamie

Absolutely.

Sponsor Message

This episode of The .NET Core Podcast is sponsored by configcat.com.

ConfigCat is a feature flag service.

- It has a central dashboard where you toggle your flags visually.

- Hide or expose features in your application without redeploying code.

- Set targeting rules to allow you to control who has access to new features.

Easily use flags in your code with ConfigCat libraries for .NET and 9 other platforms. Get builds out faster, test in production, and do easy rollbacks. Release new features with less risk, and release more often.

With ConfigCat’s simple API and clear documentation, you’ll have your initial proof of concept up and running in minutes. Also, train new team members in minutes and don’t pay extra for team size. With the simple UI, even product managers can use it effectively.

You can try it out with their forever free plan. Or get 50% off any paid plan with code NETCORESHOW.

Release features faster with less risk with ConfigCat. Check them out at today at configcat.com

Jamie

I do like the idea of splitting a request into, like, let’s use that example earlier on about a user with orders and payment details and billing details, right? Let’s imagine we’re looking at Amazon, right? You’re looking at your orders page. Nowhere on that page, does it list your payment details, right?

Alexey

Yeah.

Jamie

Because each of those orders could use potentially different payment details. And they could each use potentially different billing details. So why pull all of that data back, right? Make it as small as possible requests that you can. And the majority of things if you’re working in the browser, or if you’re working with a HttpClient, you can parallelise those almost infinitely, right? I mean, there is an upper limit on the number of tasks and how much CPU time you can actually use. But for the majority of cases, you’ll be able to parallelise it and make it more optimised. By having it work in parallel, “you’ve got a customer ID or you’ve got a user ID. Okay, go get me all of the orders. Now, whilst that’s happening, go get me all of the payment details or go get me all of this thing or go get me all of that thing,” because you don’t need all of it all at once. Because, like you say, you’ll very rapidly run out of memory or you run out of bandwidth or you run out of API requests, if you’re doing it all as one big lump.

I mean, I mentioned it earlier, when you put a request into an API, you may have to sit and spend until that API puts in a request to for other APIs. And I hate to use buzzword bingo, but this idea of, “I’ll request, just the information I need, and then I’ll do something else,” sounds awfully like a microservice, you know. Microservices are good, and they have a uses. Not everyone should move everything to them. But this idea of taking an API for what is essentially people think as an important feature of the internet, you know, YouTube is kind of an important feature of the internet.

Alexey

Yeah

Jamie

And breaking that down into a micro service. Makes perfect sense to me. Maybe you just want the comments on a video. To get just the comments, do I need to get the video itself?

Alexey

It’s very important to understand that if straightaway because you might think like, “okay, I can actually get the comments together with the video. So why make the second request at all? Like, I could save time, I could maybe even make the performance better, because I would make only one request.” And then you do it. And then suddenly they remove the comments from that; actually happens very often. So I get things moved across, you know, the API boundaries all the time. And then you’re stuck, because now you have to make two requests. But some people might not want the comments, but you’re not forcing them to wait longer because you’re now making two requests. And if you did, like, split it ahead of time, because those are logically separate, you wouldn’t to have that problem anymore.

Jamie

Exactly, right. And like we’ve said here, you know that it makes sense to do that. Because if you’re working with some blackbox API, like the YouTube API, maybe you’re using an undocumented API, which is more than likely the case you are brought in to work on something. And there’s this blackbox API is out there and there’s no documentation because it was written 15 years ago. We’re seeing this a lot in the COBOL space: there’s a lot of banking and finance applications that were written 30/40 years ago that quite literally the developers are not alive anymore. Right? And they need new features adding, or they need to fix a bug or they need support to something

Alexey

Funny you mentioned Netflix, I actually heard a story from someone on the conference, that we mentioned, like networking stuff. So he was actually working in one of those companies, I’m not sure whether it was Netflix or not. And they had an API that was used across their mobile app, or their TV app, their, you know, desktop web browser app and stuff like that. And so it was a lot of services depended on it. But it also had this weird API structure where it would return different responses on one endpoint, that you can’t just deserialize it to one thing because sometimes it has those fields, but sometimes it has some other fields. And nobody was willing to change any of that to accommodate, I don’t know, ReST standards, something like that, because it was used by everything. So the developers have to adapt and do exactly, essentially what I’m doing. And they actually do that for, you know, for theie job. So it’s a real use case that is exists.

Jamie

So this is the potentially thorny question, right. At any point in our development career, we’ve all worked with these API’s that where there’s almost no documentation or there’s some undocumented effect, right. There was one API I was working with, within the last two I’ll say, where you would post data to it, and it would respond with an HTTP Okay, but inside it would have a status code of 500 and an error message. What I’m getting out there is that obviously, you’ve received this Okay, back. It doesn’t necessarily mean that is okay. Because you’ve got to literally look at the message, right? Well, I’ve received a 500 within okay inside of it.

Alexey

Yeah, that’s actually tricky. One of the things I’m also kind of dealing with is because I don’t always have to have like JSON in response. Sometimes I have to also scrape some HTML or data from some HTML pages. And because of that, for some reason, when you have, you know, just pages returned to you, they always have status codes that indicate whether they were actually successful or not. So you have to also look inside of it to figure out whether the response was actually successful responding: should you try to parse, or maybe you should retry and get another one. And also, like, one of the things I did to make this simpler is I made a sort of a middleware in my I have like this, you know, request pipeline. So I inserted a middleware for different kind of requests. And you know, if it knows that it’s a request to this URL, it knows that it could return a 200 Okay, but it might have something inside. So it’s first looks into it. And then if it actually isn’t successful, it tries over again. So from like, the higher level, you don’t even realise that’s happening. So you have those. That’s not redundancy. What’s it called? Resiliency, I would say yeah.

Jamie

Like we said at the beginning, working in these sort of open source areas, helps to… more than likely your work on YouTube Explode has affected how you think about accessing external API’s in your sort of day to day, “I am being paid to make this”

Alexey

For sure. Sometimes there’s just like when I have to make a request, I’m like, “should I really deserialize this to a class? I mean, maybe I should just use like LINQ to JSON or, you know, just parse it manually, it would be safer.” I’m really starting to wonder it every time.

Jamie

Sure, I totally agree. I don’t want to say this in any way, in a bad way. But I have noticed that NewtonSoft JSON has become like, it’s required to do any kind of .NET work.

Alexey

Yeah.

Jamie

It’s one of the reasons why I think Microsoft hired James Newton King, it’s because your libraries required to make it all work. In fact, it for the longest time it was a dependency for ASP. NET Core: you needed it to actually receive the requests as they would handle the conversion to and from JSON for you. I mean, it’s a well written library. I’ll say that.

Alexey

Yeah, for sure.

Jamie

But there’s a lot in there that, like someone will pull in there, and it’s maybe a 15 16 17 megabyte NuGet package - and that’s pre compiled and optimised - and they’re using Deserialise<T> and that’s it. At which point you may as well use System.Text.Json or like you say, hand roll the parsing yourself, because if you need to be a small and tight and just deal with this one object, why not write it yourself? Right?

Alexey

Right. One of the solutions like to the problem when you have like a response from a service, and you also want to return something to the consumers in a different schema. One of the solution is to have like a DTO object, right? To kind of that and you also have a separate response, but I really done like this duplication where you have two layers, sometimes even three layers if you include the entities on the database side. So by just doing the deserialization manually, if you have, for example, you know, a property that has a different name on the other class, you’re could actually do the same, but you don’t have to create and duplicate all those properties all over the place.

Jamie

Sure, because then you end up with, if you have multiple copies of a like a DTO, and then a database and seeing all these hundreds of different things, you end up with: “well, I have to change it here. And I’ve gotta to change it there. And I gotta change it there.” And then if you’re unlucky enough to be using, say, a mapping library, like say, AutoMapper and don’t have unit tests for that, it blows up in production.

Alexey

True, true. We actually had a case at work where our contracts were like in a separate project that was pulled using sub modules, adn then that project is also used in another project. So actually changing something in one model in the contracts was very difficult. You had to make a change on the one client I would say, then you have to make the change on the contracts, and on the other service and you have to pull the sub modules. You also have to like publish some NuGet packages. At some point. I remember I had to make changes in six projects, just to do that. That was crazy.

Jamie

And that’s the worst, isn’t it? Because like, if it is an API that you’re calling, it fails, when you run it, you can’t, whilst building, you can’t put in an HTTP request to make sure it comes back, because then you’re writing three times as much code, just to actually test that the value comes back directly. So unless you’ve got like an integration test, but then it gets a bit wobbly, because if you do write that integration test, but it is broken, is that a failed test? Is that a failed build? And then, like you say, you pull the git sub module and it’s changed again, or that sub module requires another sub module, which has changed, it’s turtles all the way down.

Alexey

Right? Whether the integration tests failing is like a bug like you said, or something else failing. It actually it depends like on the responsibility on the service, like what is actually supposed to do. So for example, I usually fix but I also have tests that verify that whatever it is they’re doing, they actually can do. So if YouTube changes something they start failing, right. And that’s actually a good thing. It might not mean that there is a bug in the library most likely doesn’t mean that. But on the other hand, I get this early warning that one of the let’s say 50 methods doesn’t work anymore for this particular video because sometimes like 15 videos, you might get an error and one of them. And if that’s like your scenario, if one of your service is doing is actually something like that then, integration tests are much more important than any kind of tests really.

Jamie

Definitely. In that case. Do you have any specific advice to people who maybe looking either they haven’t come across it yet, or they already have an they’re struggling with it, or they’ve already dealt with it, what would be your advice for dealing with these kind of bakbox API’s? Is it just a case of split your request down to as many small pieces as possible, and hope that it still works? Or was the Alexey way of surviving? Creating YouTube Explode?

Alexey

Yeah, so in retrospect, I would say that, you don’t want to think about how all those like requests you can make actually a look, and the responses, you’ll want to think about what do you want to give to the users. And from that perspective, you can model your API like as if it was wrapping a REST service. So for example, in my case, I actually had to inspiration from OctoKit, which is a library for GitHub. And they have this sort of layered client that you can like go to branches and their requests related to that. So I took that inspiration, I actually made the same thing, even though the actual API I’m talking to is nowhere close to being REST. I model it like that. And I try to make my models the way I want them to be. And then I adapt the request and parsing so that it fits into that model. So not the other way around. Because I realised that I want to reduce the risk, right. So I want to also, like you said, split them apart so that they’re a small as possible. And how would you do that? I basically think that I think about, for example, what you’re dealing with, if it’s a video, there could be like you said, comments, there could be something like title, and a rating or something like that. You can think about it for yourself like, “is a comment something that you would always want to get along with the video? Probably not right? Would title be something you always wanted to get with the video? Probably yes.” Because, you know, it’s one of the most important metadata properties. So you probably keep the title on the video, but leave the comments to some different requests, or something like that. And by doing that, you’re essentially making it more modular and without losing usability because of that. And if something does break, which eventually happens. It’s easier to fix and your users don’t suffer as much because the other requests might still be working as a lot better this way.

Jamie

Sure. I totally get that. So one of the things I do for one of my many little web projects is I allow embedding of YouTube videos. If you embed a YouTube video, you don’t care about the comments, because you’re not going to read them.

Alexey

Right.

Jamie

All you need is an image to display with the YouTube play button. And when you click the play button it needs to start playing, right. You don’t need view count, you don’t need thumbs up and thumbs down, you don’t need comments, you don’t need the related videos, you don’t need “what playlist is it in?” You just literally need the smallest piece of data. And like you say, if for instance that API breaks, but the comments still break, you can still display the comments.

Alexey

Yeah.

Jamie

But you can display a maybe a message that says, “unable to play at the moment, please try again in a minute,” or something. If I’m completely honest, I think this advice extends to not just, “I’ve written an API, which scripts an API,” {but like I mentioned earlier, let’s say your Entity Framework or Dapper, or Debonair, or something. You’re interacting with a database via an API, right? You want to make your requests and responses as small as possible. It doesn’t matter if you fire off 1000 of them, as long as they are just pulling back two or three bits of data. Because the data that you receive may be completely unrelated. You don’t want to pull it all back at once because then you’re wasting time waiting for all of that data to come back. Right. That is the whole reason why parallel computing exists. Right? So reason where we have multiple cores and hundreds of threads on our computers.

Alexey

Sure, yeah. it for sure it extends to other scenarios as well. So it’s, it’s something you know, like one of the things about programming that I both love and hate is when you keep working on something and you have this sudden realisation, “oh, that’s how it’s supposed to be.” But then you look back in retrospect, and you think to yourself, “it was actually very obvious. That’s one of the main principles like why wasn’t it doing it from the beginning?” And like splitting things up, like you said, is one of those things that just makes sense most of the time, but somehow it might not be obvious from the beginning. So really depends on the context.

Jamie

Absolutely. I don’t know whether it translates across but in UK English, we have this phrase, “you can’t see the wood for the trees.” So wood is like a wooded area. And you can’t see that because of the trees. You can’t see the obvious answer because you’re surrounded by all of this detail.

Alexey

Yeah

Jamie

I don’t know whether it fits 100% but I feel like it kind of does. I mean, it’s like all metaphors, right? It doesn’t fit perfectly. But it kind of works a little. It gets the point across.

Alexey

And it’s also funny because I was just, you know, writing in C# for the longest time. And then I started learning F# for like about a year. And, you know, when I had problems in C# I would think to myself that “oh, that would probably be easier to solve an F# like this. This sounds like a functional programming problem.” And then when I actually started doing stuff in F#, like I said earlier in this recording that I realised that this just a different approach, but because of that, I realised that, you know, all of those things that made me think that there might be a better approach didn’t make sense because I lacked all this, you know, perspective that I didn’t have before. And it’s kind of the same was just the principles you take away from a project like any kind of experience for some reason, it always seems obvious in retrospect. And sometimes it’s even a little bit embarrassing, like you want to like tell it to somebody and you start talking about it. And then you think, “maybe they’ll think I’m stupid, because that’s how you’re supposed to do it,” right. But yeah, that’s that’s how it is, I suppose.

Jamie

Well, I mean, if you’ve never experienced it, then you don’t know. And the way I feel about it is, I always try to question my assumptions, rather than saying, “it has to be done this way.” I’ll ask well, “why does it need to be done that way? Is there a business reason for it to be done that way? Is there like a constraint?” in like a, we don’t have API contracts? Is this an API contract that states it has to be done that way? Is it a framework or a tooling or language specific thing? If not, has, has there been exploration into other ways to do it? And if there has, what were the results? And if there hasn’t why not? Let’s take five minutes and figure out another way to do it.

Alexey

Right. Something that happens sometimes is when you think that there might be a better way to do it. So you start on this, I guess, goose chase of a better way of doing it. But then you realise that the first way you find that was actually worse than some other way. So they started looking for a different way. And you keep going, going, going, and essentially you end up with something that’s very similar to what you’re started. On the one hand, you realise that, “okay, the first, you know, design wasn’t that bad. On the other hand, I wasted maybe a week trying to figure out how to do it better.” So it’s kind of like a mixed feeling. On one hand, you’ve gained experience. On the other hand, you also didn’t really make anything better.

Jamie

I can understand that. From my point of view, if I ever end up in that sort of situation. I’m always trying to do things as effectively for the people that I’m working for and with. I try to stick away from the word “productivity”, because for some people productivity is, “I have a Kanban board and I’m moving the post it note from the left to the right, or in different cultures from the right to the left. And that’s all I care about, as I move the post it note,” that’s what productivity means. Whereas for me effectiveness is, “how can I create a solution to the problem? Not move the card across, I want to create the solution that the customer, the client, whoever it is, thinks that they want.” And if that means it takes a week for me to figure out that where I’m going is wrong, that’s still effective. Because as long as I document, “hey, I tried this way, and it didn’t work,” then that means that maybe other developers in the future will come to that and go, “right. He said it didn’t work because he went this way. So we’ll go back this way.”

Kind of makes sense, to me anyway, that as a society, we haven’t gotten this far in life by people just accidentally figuring out how electricity works. It has always been experimentation. “What happens if I do this? What happens if I do that?”

Alexey

Yeah.

Jamie

And that totally makes sense. And

Alexey

most of the time, nothing happens.

Jamie

Exactly right, exactly.

Like when I first got into the study of programming just outside of high school days, you know, my tutor at the time said, the one thing you need to remember about programming languages and frameworks and stuff, is that it’s like playing with LEGOs, or whatever kind of local equivalent of :LEGOs is. I don’t know whether I get a copyright strike for that, but it’s like playing these toys that clicked together to make something. And they’re completely modular, right? If the sorting algorithm you’re using isn’t fit for purpose, maybe it’s O(N 2) or something, and you want to get an O(N), then go have a look at other sorting algorithms. And the only way you’ll find that out, is to literally go and play with the other sorting algorithms or to play with other API’s or to play with other bits of code. How else you’re going to know? So I always see that if you end up going down a path, like you said, you end up on a goose chase. As long as you have learnt at the end, why it was a goose chase. That’s a net positive, always.

Alexey

For sure.

It’s actually also interesting because, like you said, like if you were sorting algorithm as a fit for purpose, you might look at some other solutions and approaches. And sometimes you might not find you know what something is actually better or something that’s fit for your purpose. And that’s how you also end creating something new. This also like going back to CLIWrap, that’s how the piping thing actually was builT: In that I looked into how it was done in in .NET and other platforms. And I really like didn’t like any of them for different reasons, really. So one of the main concerns I had that I wanted to separate the construction like of the pipeline from the execution, and none of them really did the way I really wanted it to be. And it was really like this goose chase I was talking about that went back and forth and around trying to figure out how should I design the API, because they wanted it to be both simple for very simple use cases. For example, when you don’t want to pipe anything, just run and it should work very simply. But on the other hand, I wanted to make the more complex stuff possible and ideally also simpler than otherwise, right.

Like just designing API’s, and one of the things I really like about open source is that I can just turn an idea into like a library or a project, and suddenly after a few months, there are people who are using it. And suddenly I have to start thinking about it from a little bit of a different perspective like, “what my users would, you know, want from it? How would they use it?” And like with CLIWrap, I sort of realised that most of the people don’t really care about piping, like you said, they just want to run a CLI application. And make sure it doesn’t deadlock or just output stuff and and it works. But on the other hand, there are like 10%, who would want to make like complex pipelines scenarios and stuff like that? How do you actually make something that fits both of the use cases without hurting usability in either case, really? And it’s really difficult. It’s really fun and interesting to do that.

Jamie

I completely agree. I have a love hate relationship with issue reports on any of my open source projects. Because I’m like, “I love that someone’s found this bug, but I absolutely hate it.”

Alexey

Yeah, that’s true. It’s like, “thank you for using it. But…”

Jamie

“If you could have not reported that would have been better”

Alexey

Sometimes somebody may make a pull request. On one hand, you think, “oh, cool, somebody actually contributed to my project.” But then on the other hand, you realise you have to review it, you have to maybe, you know, brainstorm different designs to help figure out how to fit this feature into the whole project. And when you start thinking about it, that could be actually a feature that you personally wouldn’t even use, but somebody else wants it. And from that perspective, it’s actually it could be very difficult. Yeah.

Jamie

Sure. Yeah, sure. So where is the best place to find out more about both CLIWrap and YouTube Explode? Is it just GitHub?

Alexey

Yup. I try really hard to make comprehensive readmes. So yeah, I’ve tried a lot of stuff there. If for some reason, there are no answers to what you’re looking for. You can always message me on Twitter, and I’ll reply, obviously, I’ll help you. So yeah.

Jamie

Cool, okay. They’re open source. Right. And you mentioned earlier on about pull requests is that, are you actively accepting pull requests? The reason I bring that up is that I know there are a lot of open source libraries where you can make a pull request and they immediately deny it. “No, that’s not where this project is going.”

Alexey

An ideal scenario is when the user who wants to contribute opens an issue first. And that’s a good opportunity to discuss whether this is something that actually needs to be addressed. because like you said, it might not be something that the project needs, because they’re maintainers thing that wasn’t designed for that. And the person can save a lot of time by not trying to make a pull request by just asking whether it’s something you know, that the project might need.

Now, on the other hand, is also a good place to discuss how you would actually want to fix that or address or like implement the feature so it could discuss the API, you know, the lower level implementation. And if that happens, then you know, everything is perfect. That doesn’t often happen, because people are kind of random, so some people still make pull requests out of the blue. Often, sometimes I have to close them because that’s, you know, one of the reasons because this is an probably like a lot of overhead for something that I don’t really see a lot of benefit in, you know, stuff like that.

So it’s really pull requests are really I have a love hate relationship with them, because on the one hand, it’s something somebody wants to contribute. On the other hand, once they merge it is suddenly your problem. And you have to think whether you actually want to take responsibility for that. And on the other hand, also, if you decline, you might be that open source developer that declines pull requests, you know, you don’t want to be that either. So it’s really difficult to thread this balance. And at the end of the day, you’re just doing something that you personally just want to do for fun. And you also have to take into account this emotional aspect of it like balancing your answer perfectly. So that doesn’t, you know, offend the person. If you’re trying to decline pull requests or something. On the other hand, you also have to do this. So it’s really, really stressful, you know?

Jamie

Sure. I totally agree.

Okay, so what about catching up with yourself then what’s the best way for folks to [do that]?

Alexey

Twitter and I also blog on my website I’m mostly just write about things that I find interesting or niche. I really like covering very niche topics, like, my most favourite one was probably how I discovered [monadic parser combinators](monadic parser combinators). Like how you can compose a parser using functions. And, you know, this is the kind of stuff I write. So if you’re interested in that, you can check out my blog as well.

Jamie

Cool. Okay, excellent. Well, I mean, all that really remains to say is, thank you again, for taking some time this afternoon. This was a really engrossing conversation. I really enjoyed it.

Alexey

Thank you.

Jamie

There’s so much about API design that I hadn’t even really consciously thought about, and a lot that I hadn’t even crossed my mind. So I think I’m going to take a lot of points from this. And go have a look at YouTube Explode and see how that’s breaking things down and maybe my next API will be a lot smaller.

Alexey

Thank you very much for inviting me. I’m actually really glad that you found that very useful this discussion. So I’m really glad to be here.

Jamie

Awesome. Thank you ever so much.

Alexey

Thank you.

The above is a machine transcription, as such there may be subtle errors. If you would like to help to fix this transcription, please see this GitHub repository

Wrapping Up

That was my interview with Alexey Golub. Be sure to check out the show notes for a bunch of links to some of the stuff that we covered, and full transcription of the interview. The show notes, as always, can be found at dotnetcore.show, and there will be a link directly to them in your podcatcher.

And don’t forget to spread the word, leave a rating or review on your podcatcher of choice - head over to dotnetcore.show/subscribe for ways to do that - and to come back next time for more .NET Core goodness.

I will see you again real soon. See you later folks.

Useful Links

- Alexey on Twitter

- Alexey’s website

- CLIWrap

- WaitForExit

- ClickOnce

- Squirrel

- OWASP Recommended Security Headers

- OWASPHeaders.Core

- An ASP .NET Core Middleware used to inject OWASP recommended security headers into HTTP responses

- YouTubeExplode

- PHP explode function

- System.Text.Json

- NewtonSoft JSON Deserialise

- Design by contract

- LINQ to JSON

- AutoMapper

- OctoKit

- Dapper

- Debonair

- Can’t see the wood for the trees.